All right, let me do the formal intro, and we will get going.

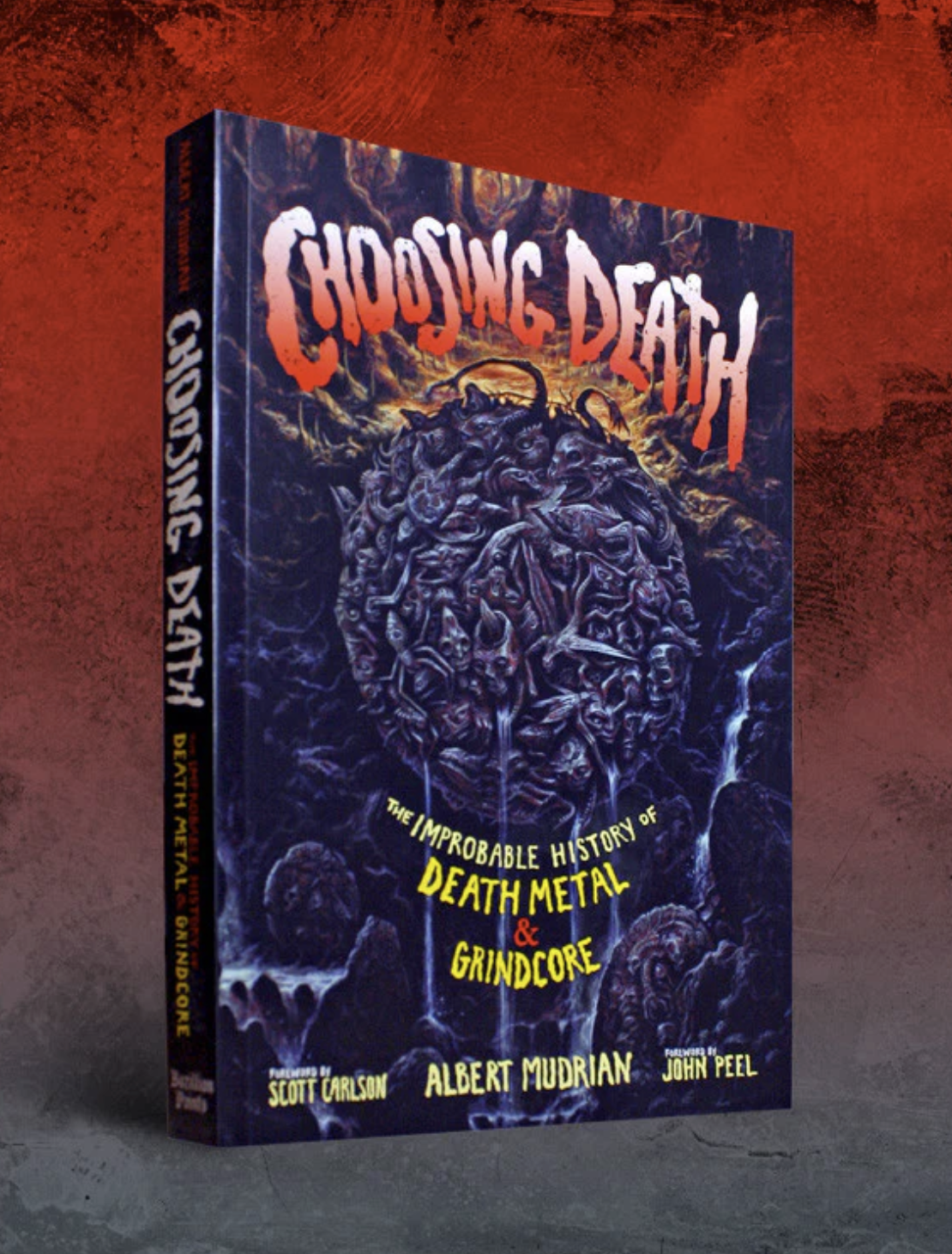

Awesome. Hey, everyone. Anthony Fantano here, Internet's busiest music nerd. Hope you are doing well. Today, we are going to dig into an exclusive conversation, one that I'm pretty excited about because it is rooted in one of my favorite music reads of all time, this fantastic book, of which there are numerous editions and translations, Choosing Death. It is an in-depth exploration of the origins and history of death, metal, and grindcore.

We have the writer of the book here, Albert Mudrian, who's also the editor-in-chief of Decibel Magazine, a long-time critic and analyst in the world of metal. Basically, I just wanted to have Albert on to discuss the book and everything in it, and everything that has happened in the wake of its original writing, its repressing in the worlds of extreme metal, and just how he sees the evolution and existence of the genre today. And that's pretty much it.

Anthony: Albert, thank you for coming on and taking the time.

Albert: Pleasure, man. Thank you for having me.

Anthony: As I was telling you before we started the interview, for a long time, this has been one of my favorite reads when it comes to just music history and analysis in general. And you just have so many great interviews and conversations throughout the book with so many important figures for this genre that, honestly, before reading this book, it was difficult for me to piece a lot of the important information together because so much of the early death metal scene and its inception was based in the underground in such a deep way, the tape trading scene and everything like that. For those who are younger and maybe less acclimated to that time period when this music needed to thrive on a totally different plane than what people are used to today in terms of Spotify and the internet and music streaming. How was this music and how was this sound getting out there, being shared? How are people stumbling upon it before even a time when bands such as Death or Atheist were taken seriously enough to be considered by a label and get signed and actually have their music physically printed and released and sold to a commercial audience?

Albert: So you're talking probably the mid '80s, early '80s into the mid '80s, post-thrash explosion, post, I'd say, the early German thrash stuff. There is a generation of kids sprinkled throughout the world, some pockets in the US, some pockets in England, pockets in Sweden. And they're linked pretty much by underground fanzines and some of the bigger international metal magazines that would have little pen pal things and little ads for pen pals in the back of them. I used to call them penbangers, I believe, back in the day. And that would just be kids who would get in touch with one another who had this interest in taking these extreme sounds, whether it was like thrash or super fast, hardcore, and just accelerating and making it even more extreme. And they all had this similar desire coming from, I'd say, a pretty similar, just like middle class, working class background. And they started making really crude demos. They started sending them to each other, making their way across the oceans, back and forth. And these kids, they would build up lists of demos. They would have this old-school demo list that they would mail, trade each other.

Anthony: People would go through it and be like, 'Okay, I don't have that Mantis demo. Can you send me that? I'm going to send you this Executioner demo in exchange for that.' And it was really like if file sharing had a give and take, if the early days of Napster were set up in a way where you basically had to upload something to download it, it would be that exchange. So that's what really built that network of what were essentially kids. Everyone was essentially a teenager, with perhaps the one exception of Eric Records founder Digby Pearson, who was a little bit older, and he would go on to be one of the first labels to really start to take a chance on some of these bands.

Anthony: What are these pen pal connections and lists and archives of demos that fans are building up and offering to each other for sharing and trading and that thing? What information were some of these fans going off of when choosing, 'Oh, I want this or that or this other thing?' Was there any writing or greater context or information on these things? Or were people just being like, 'That sounds like a cool title. That sounds sick. I'm just going to go for that?'

Albert: I mean, there's a lot of that. Depending on who you're trading with, though, you could have just pretty much the basic explanations of thrash, death, super fast, and versus something like, and I'll just use this as an for example, it's not even contemporary anymore because this is over 30 years ago now that I think about it. But it's almost like the old Relapse mail order catalog from the '90s was infamous for having very detailed and humorous descriptions of bands that wasn't always spot on, but it was potentially a small paragraph about a record that accompanied the listing of it. But back then, if it made it to that list of the tape trader, I think the network probably just trusted the ear and the voices of somebody who had it on their list. Because keep in mind, it was like, they would write letters to each other back and forth, too, talking about their own band. I've seen a lot of some of these early letters, especially some of the Chuck Schuldiner letters that were passed around where he would sign off Evil Chuck in 1983 when he's including a Mantis demo to somebody who has requested it, and you would read where it was recorded, when they recorded, who was on it. So sometimes it would be that level of detail. Other times it would just be odd. It could really vary.

Anthony: No, I mean, again, it's just so insane to compare that to the obviously digital networking capability abilities that people have today and the way that this web was able to come together just through pen and paper. And it's through these networks that, as you talk about in the book, that this sound was able to catch on and actually influence people on a global scale. And you mentioned some of those hotspots culturally that had some of the biggest bands and some of the most, I guess, healthiest scenes in the genre. But in the book, and as many who are into death metal know, some of the biggest groups and most significant records came out of the Florida scene back in the day. Moving forward a little bit from those early tape trading days, what in your view, because I always wondered this a little bit, what in your view is culturally or contextually, what made Florida exactly the place that ended up being, I guess, just such a hotbed for this sound, because when you listen to some of those classic death metal records, I don't think a lot of fans would necessarily associate that sound with a sunny, warm, humid Florida. It doesn't exactly, on the surface, seem exactly like the vibe or weather-wise, the perfect setting for this very gnarly and aggressive sound to be evolving and growing in a petri dish in such a profound way.

Albert: I don't think there's just one specific factor. I think it's like any situation, there's a number of variables. I think the fact that there was a band that predates all of the death metal band called Nasty Savage, which when I was interviewing bands for the Florida part of the chapter, whether it was talking to Morbid Angel or Atheist or Obituary or whomever, all of them would really give a shout out to this band as this crazy extreme band that was never really made it out of the Tampa area at the time. But they'd be a guy would be wearing TVs on his head and bleeding profusely all over the crowd. It was just a really early prototype that showed a bunch of kids like, 'Oh, I could get up there and do that.'' This stuff is crazy. It wasn't that cool yet, but it was something that I think at least that was something that helped galvanize some of those kids, especially because the band Nasty Savage were always welcoming to the younger bands and trying to help them out about, 'Here's how you fly for a show, here's where to go to record a demo,' which is another important variable to the whole development of the scene, and that is more a sound studio Studios, which is located in Tampa. It became the go-to... It would eventually, in the early '90s, become the go-to place for bands who had full-length records to record. But even prior to that, it was still one of the few professional recording studios around that if you were able to go in with an engineer by the name of Scott Burns, you wouldn't have to pay an exorbitant amount of money to go track three or four of your songs. You had an engineer there in Scott who was somebody who came from a punk background who saw these kids that were typically four or five years younger than him wanted to help them because he saw this death metal stuff as an extension of the punk stuff that he was into. So he didn't dismiss it as a bunch of kids making noise. He accepted it and embraced it and really tried to nurture those kids into being able to give them a decent product that they could eventually send out to labels and gain that interest. When you got a couple of bands who just... Some of it is the happenstance of we're in Florida. If you're 15, 16 years old and you're not at the beach or you're not at the water park, maybe there's not a whole lot to do. If you're not a jock, if you're not playing football or baseball, you're going to eventually gravitate, I think, towards music. I think that, like I said, that happenstance of there just being just enough like-minded musicians who were around and then having essentially an infrastructure to thrive got it off the ground. Something to consider is that back then in the '80s, there were still so few death metal bands that if you had more than one band in a geographical area, immediately it was a scene because there was still so few people playing it or listening to that stuff at that time. I think when somebody basically puts the thumb tack in the map and says there's something going on here, even if it's just something not that big, eventually it's just going to grow the second that it's been recognized.

Anthony: You also talk about in the book, and you mentioned just there, the connections and esthetics, the genre in a way borrows from punk music, which I think a lot of people often overlook in terms of the rubric of the genre. If you could dig a little further into, I guess, for people who are uninitiated or even those who are familiar, trying to put into context, because it has been so long since these days, what exactly I guess this genre is born out of in terms of its cultural and its ideological context. I guess what I'm asking is, death metal, to perceive it merely as just an ongoing series of evolutions in metal where you obviously have fans and artists who are like, 'Yeah, we got to make something heavier, faster, more extreme.' Or in a broader sense, is this genre of music an answer to something that's happening broadly in the world or the country at the time. I mean, obviously, we're also coming out of a time where you had the PMRC and the religious right and the Satanic Panic and so on and so forth, which obviously a genre such as this like, flies in the face of in terms of its blasphemy and its extremity and stuff like that, which I think is often overlooked for a lot of younger fans who are coming at metal without necessarily understanding the cultural battles that needed to be fought in the '80s and '90s in order to legitimize this music in a way to where it wasn't shoved into the corner and treated like it's a danger to children and stuff like that. Are some of these bits of cultural context inspiring the artists who made these records and driving them to go in the directions that they did artistically, or was it merely just a love of the sound?

Albert: Again, it's a little column A, a little column B. And it really depends on the artist. If you want... So let's take two bands, for example. Let's take Napalm Death, who clearly, their roots, they started off as... When they started off, they sounded like crass. But as as time went on, and they got members who were... Because their membership, that's probably a book in itself.

Anthony: It is. You even talk in the book how essentially the personnel on the first side of the record is pretty much completely different than the second ride of the record, which knowing that, you can actually hear it when you listen to the album. But yeah.

Albert: So as they evolved, they evolved out of punk, and they were playing within a very short period of time, they got metal players, and they were playing extreme metal, but they still had this punk rock ethos and lyrically, a really socio-political just awareness that you're not going to find on a record by, say, Cannibal Corpse, where we're going to sing about zombies for a little bit. Napalm Death don't have any songs about zombies, but that's okay because there's an element of horror in straight up death metal, I think. You know what I mean? If you're coming out of even the Satanic elements of, let's say, a band like Morbid Angel or Deicide, there's theatrics involved in the presentation of that Satanism that I think is out of influence from classic horror. Let's be honest. Did these kids eventually find a copy of the Necronomicon? Sure. But did they find it before or after they saw the Evil Dead? What do you think? You know what I mean? So there's this element of that traditional horror and pushing the envelope of things that people say that adults would claim are bad for you, whether that's Satanism, whether that's horror movies, whatever feels dangerous. So you have that, but you have this natural, youthful, aggression that comes with being, I think, just... Because this scene was 99% young boys. That just naturally develops out of that time in a kid's life. So you have those interests. You have that just general testosterone-driven enthusiasm. But you can also have this righteous anger if you are an informed, essentially, progressive kid and care about social issues, care about the path that the planet is on. Because in the '80s, it was like, I know everybody can easily point to present times and just see the state we're in. But what we feel now, those kids felt in the '80s. They felt the same way. Whether the situation mirrored what we're in now or not, they felt the same way. So that translated for a lot of them where they grew up punks just through the lyrical presentation of the music. And obviously in the cover art, too, with like Napalm Death, there is just all this anticorporate stuff that's part of their first album cover Scum. And then, conversely, Cannibal Corpse's first album, Eaten Back to Life has a zombie, I think, disemboweling itself on the cover. And I think even at times, you would have bands maybe Repulsion who shared a lot of the politics in Napalm Death, but had all the lyrics of Death, or Cannibal Corpse, or Obituary. I think that's like... I think for some people, it's hard to process that separation and have this idea that these things can coexist. Because at the end of the day, it's still super fast guitar cars, blast beats, growling vocals. These are elements that just are across the board with all of them to some degree or another. But I do think that any scene has a wide variety of personalities in it, and those personalities are going to have a wide variety of interests, and some are going to gravitate in one direction, some are going to gravitate in another. I think that sometimes that's like... The fact that Choosing Death is called, the subtitle is The Improbable History of Death Metal and Grindcore. I think the term grindcore, in a lot of ways, just became a bit of a way to separate something that had maybe more of just a punk bass. And like I said before, that lyrical content that wasn't like, bore and horror, to separate it a little bit from traditional death metal because they both come up at really the same exact time, and the kids who are listening to one or listening to the other. If you look at early Napalm Death photos, they're all wearing Morbid Angel shirts. So it's all intertwined, I guess, is my way of saying it. But some bands, the presentation of it is very separate.

Anthony: Yeah. During that time period, and really, there's been so many different bands and artists and fans within both of these genres, respectively, have been listening to each other for years and have been starting bands that obviously fuse both. How many deathcore bands have there been at this point? Even in the additional material that you add into the book, you talk about Todd Jones of Nails being such a big fan of Deicide, for example. Them being portrayed and framed musically in the way that they are, even though a lot of their riffs are metal riffs, I think a lot of fans would presume, oh, that's probably just because they're in a metalcore, not necessarily because they're into one of the most famed death metal bands of all time. But Todd himself was like, no, actually, some of those choruses read to me like hardcore punk choruses, and it's like, yeah, the shouty bits of Deicide's classic records, they are punk.

Albert: I think that any time you're playing something that's extreme, anything that's this extreme, I think that you have to give some reference to punk because that's really this demarcation point as far as envelope pushing goes in contemporary music. And this idea also that anybody can get up and do it. But I think the thing that maybe separated extreme metal and how it developed out of punk was just how proficient you had to get after you picked up that instrument, how much work you had to put in. If you really wanted to be extreme, you ended up having to really work your ass off to play that fast, have it be coherent, have it be tight. Then some of these bands were much tighter than others; don't get me wrong. Even some of them that are still around today, you can pretty easy to spot the differences. But I think that... Yeah, I think there's even in the most... The kid who shows up at MDF with the most backpatches that are of the most obscure bands that released one record in 1989, never played a show again after that. Even that kid that only listens to that stuff, there's bad news. It's still got so much punk as part of its DNA. You can't escape it.

Anthony: You talk about that envelope pushing element that is very important in the genre. You said goes back to punk. Do you feel like death metal, and you do talk about this a little bit in the joke, but giving maybe a more current answer for 2025. Do you feel like the genre still to this day has the same amount of taboos attached to it, that it did at one time? And if not, is that as a result of a lack of creativity, willingness to push the envelope, or is the context that death metal exists in just changed and there aren't as many taboos to push right now?

Albert: I think it's probably more the latter because you got to remember, let's say, 1990, the first Nocturnus record, the fact that they had keyboards on it was such a polarizing event in that scene.

Anthony: In this case, we're talking about taboos in the scene itself.

Albert: Right. When you had those, and obviously, as time went on, and it was honestly like things developed pretty quickly. By 1995, you had so many different flavors of things and so many of these bands that had started out essentially playing cave man death metal, being really progressive and interesting and incorporating way more than traditional extreme music into their sound. But as far as where we're at in the genre now, I think it's still pretty healthy because yeah, I don't feel like that there are as many hangups about what you can and can't do. And you're always going to have fans who in their head are purists, that they only want these few set elements to be part of their formula. That's fine. Those records will always exist. You can always go back to them. You can always complain that nobody has written a good death metal record since 1991. It's fine. I don't believe it, but it's fine. But for me, personally, I do think that in terms of this idea of the genre continuing to break new ground, I don't even think that It's like, if a new band is starting, I don't think that's the impetus for it anymore, like it maybe was 40 years ago, where you were literally… This scene was literally developing at the time, and bands were doing stuff that bands before them previously hadn't done anything all that similar to. I think it's like, at the end of the day, it's still a couple of guitars, a bass, drums, and a guy growling into the microphone. I guess there's only so many ways to go with it. But by the same token, you've got bands like, to me, Blood Incantation are super important in this regard, especially on the heels of what they just did with Absolute Elsewhere. I know it's this hybrid of styles and sounds, and I've heard people compare it to Deafheaven's Sunbather, where it's like, they're not really doing anything new. They're just taking two things that already existed and putting them together. And I don't necessarily I don't necessarily see it like that. I do think that they are breaking new ground there because there isn't another record that I have that sounds like that. So once somebody is like, I have not heard that before. Well, guess what? You're moving something forward.

Anthony: Yeah. The thing is, there are so many genres that are born out of just bringing two things together that previously were not together in the first place. And on top of it, with those two examples that you bring up, it also displays how much novelty is based on audience perception. You talk about at one point a keyboard being on a death metal record being such a controversial thing. And now we have this other band, like years later, who is obviously doing the same, but on a more elevated and ambitious level. And it's hitting a lot of audiences in a way to where they're like, 'Oh, you could do this in death metal?' There are a lot of old-school fans that are appreciating the record, but the band's fan base, at least from what I can see, mostly seem like just very young, excited fans who are just getting into music, generally, that didn't know that you could do this stuff with metal music like they're doing.

Albert: Yeah, there is definitely... They have plenty of fans that are old-school death metal fans or middle school death metal fans. I don't really know what it is between that and the kids. There are plenty of people who that might be the first death metal band they hear, and like you said, the reaction is, I didn't know this stuff could sound like this. I think that's to me just that mark of a healthy scene that even one band, still 40 years after the birth of the genre and the style that they can do that and rethink things. And don't get me wrong, I think they are much more the exception to the rule than most bands coming out. But I think that's the case of any band that's doing something that's legitimately great.

Anthony: Yeah. I mean, as much as we praise that record, like you just said, I still haven't heard and still not currently hearing a lot of albums that sound like that album. And with that being the case, do you feel like the main function and focus of the genre is still to be locked into this almost, I guess you could say, arms race of volume, speed, intensity? Or do you feel like the future of the genre, creatively or in terms of its audience demand, is more in terms of figuring out ways to subvert expectations? For the most part, do feel like fans are still demanding of death metal today, what they did maybe 10 or 20 years ago, or are the demands and interests and expectations different now?

Albert: I think for the first part of that, it's more the latter in that the arms race is kind of over. There's really only so fast you can play. You run out of space and time. It's just like you can only get it so fast.

Anthony: There's only so many drum hits you could put in a single fill. Right.

Albert: Unless somebody can develop a formula to alter time, they're going to have some difficulties pushing that part of the envelope. I think you can talk about even... If you want to talk about other extreme metal subgenres that are essentially owe a large debt to death metal, whether that's black metal, whether that's metallic hardcore. I think it's more of that, if you want to talk about that envelope pushing in that sense, where it's just this stuff is just developing out of out of this genre, whether the genre is getting the credit for it or not. You know what I mean? And that's fine. But I think you see more of that. But in terms of actual audience expectations, conversations, and desires from what they want out of death metal bands in 2025, I think, again, it goes back to the genre having 40 years of history, and there being plenty of different established avenues you can just go down with it. Are you a tech death band? Are you a melodic death metal band? Are you this retro old-school throwback death metal band? You can decide what death metal band you want to be at a certain period of time. Then where your creativity takes you, it's up to you. But as for fans, I think there's always interest in the legacy bands of the genre, especially the ones that are continuing to make competent to actually really good records. I've got to say that for me, death metal has way more of those than most sub-genres that I have run across. I'm not trying to say that the new Obituary record is as good as Cause of Death or something, but I will say that I'm certainly going to listen to that Obituary record more often than I would listen to whatever the hell the last Radiohead record was versus The Bends or OK Computer. I just think that even though bands evolve and develop and sometimes stray incredibly far from the path. A lot of those bands should be acknowledged and rewarded for doing so. A lot of cool developments have come out of bands who were started with death metal bands and then just evolved into something that had nothing to do with the genre. But at the same time, I think that for all of the legacy bands, that route is still there. That, I think, is probably the most important thing to the fans of the genre and their expectations of the genre. It's like, is there still that red line that you can draw between album 1 and album 12? If stuff happens in between in whatever direction you're going in, that's cool. But can I still see my way back to this, and I think with this music, oftentimes, the answer is yes. I think for fans, they're just like, maybe it's a lower expectation, but I also don't think death metal fans are looking for the same thing out of every one of these types of bands. I don't think a Blood Incantation fan is looking for the same things that a Cannibal Corpse fan is going to for when they go buy the new Cannibal Corpse album. Their expectations are going to be different than the expectations of the fan who's going to buy the new Blood Incantation. And that's fine. That's cool.

Anthony: I wanted to ask you, one of the most interesting points of the book for me are a few of the chapters toward the end, very specifically, like an interview, a conversation you had with David Vincent of Morbid Angel, where he's talking about that point in the mid '90s where he was going to depart from the band after a tour they were doing at the time. And he's reflecting on the sound of the band live and how everything's perfect. And it's like, we really got everything down and really nailed it. It sounds loud. It sounds intense. All the drum triggers are perfect and this and that. But I'm just disillusioned. I feel numb. I don't feel anything listening to the sound anymore. I don't really feel like we're getting the same reaction from the crowds that we did at one point. And he's not the only voice from that era that expresses a similar sentiment around that time. That numbness that maybe certain artists in the genre were all feeling coincidentally at the same time and falling out of favor with it for a little bit. Do you feel like that time period has been totally transcended? Is that period of numbness completely over? Do you feel like there is maybe a certain amount of death metal that you could expose yourself to, to where the genre just stops doing much for you. Obviously, you're still passionate about the genre after all these years. And do you feel like the variety that you're talking about that we see in the genre today, has that fixed the problem? Because now we're not hearing just one or two or three different styles of death metal. We're hearing a very wide variety of different bands that are all doing different things.

Albert: I think it depends on who you are and where you're at in your life in a lot of ways. I think that for those bands, when he talks about that experience, I think he's referencing somewhere around 1995, 1996. We're talking for Morbid Angel. I think he was in Morbid Angel in '86. So, he's 10 years into that ride at that point. And I feel like it's when you are discovering a genre, and if you're actually coming up as part of the genre, you have all that excitement of the first first couple of years, really, of discovery, of being part of something that's new and seeing where it takes you and seeing where it could go, whether you're the artist or whether you're a fan. And I think after a few years, you end up chasing that feeling a little bit. And when that feeling is gone, as it was for him then, I don't think I don't think... I just don't think he...Honestly, it's just something he knew what to do. I think there were some bands who didn't... That they saw this, but they didn't know what the next move was because they didn't have this plan of, We're going to be Let's use Carcass as an example. We're going to start out with Reek of Putrefaction. It's just going to sound like noise. And then we're going to, in our first phase, end up sounding like Megadeath a little bit on our last record, eight years later, it was maybe. I think that those times, they're a little weird because sure, there were some bands who just kept making the same death metal record over and over for that one decade, two decades, three decades. But that period where the shine of this is something new and exciting that is never done before, that's never that really happened before, when that shine wears off, where it turns into people, you split into two camps of, I'm just going to keep doing this forever, or, okay, well, what happens next? I think that what happens next period, which is really, I'd say it's about '93 to about '98. That's when I think you really had bands exiting the genre or just bringing in so many influences into it that it had so little to do with death metal anymore, that it became a confusing time that people looked at it and were just like, 'Oh, the genre is dead.' Because these bands, they didn't develop it all up within the confines of death metal in an interesting way. They had to go outside of it. But I think it really just had to... I don't even think it necessarily died out. Obviously, there are a couple of fewer records, a death metal band's fourth album than their first one in that era. So many of the most important bands, whether it was Carcass or At the Gates or whomever broke up during that period, and very few... The two that always come to mind that stayed the course the whole time for me are Cannibal and Napalm. They're through every up and down. They managed to clear every hurdle. They played the show as the 50 people at when stuff was not great. Sorry, I'm trying to pull it all back to your original question of, did this stuff have to die in a way to be reborn? And I think maybe there's a little bit of that. And I don't think it could have developed without bringing in these other influences. Because, I mean, don't get me wrong, I love Symphonies of Sickness, but I don't need 12 different versions of it over a 30-year period either. So I think that for most people, most fans in the genre, I think there are very few people who just like death metal and only like that. You know what I mean? It's like the person who... I love coffee, but I only drink it from Starbucks. They don't want it from anywhere else. And it's almost like, wait a minute. I don't know if you love coffee. You just might love Starbucks. So I think that it really is this idea that death metal fans probably, in some ways, don't even get the credit they deserve because the genre is, at this point, it's so fractured in a good way that there are all these microgenres underneath it that just because there's growling, it isn't necessarily just death metal anymore. And maybe it's the only thing that ties it all together in some way. But does that make any sense? I know I rambled there.

Anthony: No, it does. And it's bringing me to my next question that I wanted to ask you because we had this period where some of the classic bands weren't putting out their best stuff. You had less sales, less interest. But then this rebirth period in the dawn of the Internet age, where you had bands and you had older And then rediscovering like, oh, there's this new crop of fans out there getting into what we do, appreciating the old stuff. And it became apparent with the genre becoming the age that it was. There's this new generation of listeners out there who are being introduced to it for the first time, and it's hitting them like younger listeners back in the day. We're hearing it for the first time because there's always a potential to reach that new first young listener who hasn't been exposed to this stuff in a way to where maybe they would be a little burnt down on it after having heard, like you said, 12 versions of the same album at some point. But with that being said, while it is true, and I agree with your sentiment that the variety of influences and styles and the broadness of the scene today is definitely healthy and a sign of it being in a good place. But do you feel like this genre of music has adapted well in the streaming age because we see so many, or at least I cover a lot on this channel, a lot of articles and coverage about how difficult it is more extreme experimental music acts, get playlisting opportunities and be prioritized on streaming platforms that are more geared toward pushing people algorithmically to their biggest cash cows and stuff like that, and how it's difficult for sometimes more alternative forms of art to scale on the same level as the new Lady Gaga album when you're talking about a streaming platform, and how difficult it is for artists to make money off of their records on streaming platforms, especially when they are more left field. And that's a quality that's inherent in death metal. So in your experience, from what your interactions with bands have been, be it new or old, is it harder to make it financially career-wise as a death metal band in the current day and age of streaming, even though it may be a little bit easier to access your music just by looking it up on your phone or on your computer?

Albert: I think it's all about context. Let's look at it this way. Who's the biggest death metal band in the world? Cannibal Corpse, right? I think we could safely say they sell the most records, draw the most, most recognized name, biggest, most consistent discography, probably. Right? So Cannibal Corpse is going to draw a maximum of 1,500 people a night in the US. So if you want, you can compare that to what arena tours do with pop stars and stuff, it's never going to... The ceiling is still so low compared to even mainstream rock music. Every '90s mainstream rock band that had a song on commercial FM radio in 1995, they're playing every Jiffy Lube Live outdoor shed this summer, with three of them stuck together on a bill, and they'll sell 10,000 tickets. So the ceiling for this genre is still so low, comparatively speaking, when we just look at the big picture of everything that's out there. So I don't necessarily think that anybody... Sure, it's a struggle. Everything is harder. For anybody in the music industry, unless you are the top 1% of artists or obviously the people who control the platforms that spread the music, you're at a huge disadvantage. And whether that is even those guys who are playing those, even the Lives and Collective Souls who are, sure, they're doing fine. They have a career, but they're still playing. They're probably still making what they made in the '90s in their heyday, which is pretty good. But Canival Corpse is probably making more money playing out now than they did in 1996 or 1997 or even 1992 when this stuff was blowing up. But the idea that an artist, somebody who wants to make a career out of death metal, there were so few opportunities to begin with, even back at the genesis of the genre. So few things are going to break through to even get to that level of, yeah, we can go out and comfortably headline a thousand cap room. Now, there are even fewer of those opportunities because, in some cases, it's still the same bands from 30 years ago that are out there doing that. But it's also just that much harder for a musician of any type of style or genre to make an impact. I don't think it's necessarily just death metal or extreme metal or heavy metal or even rock music, because all the platforms are just, like you said, there's so few of them. It's part of the reason that Decibel exists, to be able to say, okay, we have an opportunity to platform some of these bands that we're excited about, whether it's through the magazine or live events or whatever. And because there are so few tools. It's like, oh, you can get on social media and... Oops, that's it. I guess. So, yeah, is it harder? Yeah. But it was super hard to begin with, I guess, is what I would say is a short answer.

Anthony: Right. It's just adapting to a new difficulty, I guess you could say. Things started out hard for death metal to begin with. It's just a different hurdle that it's having to jump over.

Albert: Yeah, just like getting old. Yeah.

Anthony: With mentioning what you just said in terms of obviously spreading the word about what in the genre is interesting and curating around that, what do you feel excites you as far as... I mean, we mentioned Blood Incantation earlier, but what do you feel excites you in the genre today, artist or album-wise, in terms of recent releases that people should be aware of?

Albert: Like the bands? Honestly, it's funny because if you want to bring this back to Choosing Death for a second, it was what, 10 years ago that the last version had come out, the one that's out on Bazillion Points now.

Anthony: And what I always loved was in the back of the book when I had the original version was the album list in the back.

Albert: Right. The scene that has developed, the bands that have come out in the 10 years since then that have made an impact, I think it's even better and more exciting than the 10-year period previously, which was the additional stuff that was added to that second version as a I can think of, obviously, Blood Incantation, Tomb Mold is another one for me that I just think. I'm not a big... I know these are two of the proggier bands, and I'm typically not a prog guy. So the way that they have incorporated into music that I feel is still extreme, because all the techy, proggy stuff like, man, I think it's a lot of times with extreme metal, I think it just loses that element of danger where your choruses are super clean and it's the good cop, bad cop thing that's going on vocally. It's just like, which band is this now? I struggled with a lot of that stuff. That stuff has been relevant for 10, 20 years. But for me, it's really these bands that I think, amazingly, they grew up reading stuff like Choosing Death and reading stuff like Decibel, bands like Blood Incantation, Necrot, Gatecreeper, Tomb Mold. When I got to know these guys, they've explained to me, 'Oh, yeah, I grew up with a subscription to this book, or a subscription to the magazine, or it was the book that got me into this genre.' So it's weird in a way, for me personally, to process that because it's like you're inadvertently... Well, you're purposefully, I think, obviously, with a music magazine, you're trying to recommendations. You're trying to expose people to new stuff that's happening, as well as, especially in the case of Decibel, stuff from a historical perspective with the Hall of Fame pieces and making sure that the present is tied to the past and explaining it all out to people. But in some ways, it's almost like this proof of concept because it's like, oh, wait, a bunch of good bands took some of this information and processed it and now are making things that we're excited about. These are bands, all those bands that I just have mentioned to you, they've all been on the cover within the past two years. For me, that generation of bands that have really come out, I'd say in the past 10 years or so, led by those. I can go and cite super-specific examples. This band, Ancient Death, are the lead review and the issue that just came out. But they're from, I think they're like Western Massachusetts, and they have a clear Blood Incantation influence. But the guitarist, who is the main songwriter, plays It also plays in the current version of Atheist, and I'm sure he is in his late 20s, maybe early 30s at the oldest. I guess it's just really cool, this idea that the record is innovative and interesting. Again, it does owe a debt to Blood Incantation in a way, but it doesn't… I don't listen to it. I listen to it because it sounds like Ancient Death. I don't listen to it because it sounds like Blood Incantation. But the point being that the connection of the historical and the present is just so strong in this genre in particular. I think that's one of the things that helps to propel it forward. And nobody's ever going to stop listening to... We're 40 years in, almost. Nobody's going to stop listening to Left Hand Path. Nobody's going to stop listening to Scream Bloody Gore, Leprecy. These things are just part of the DNA, but it It's still like the kids who are moving it forward get that, but they're not trying to make those records, which is, I think, maybe the key to all of this. They know those records are important. They love those records, but they'll just be like, 'Okay, this is what we do, though.' I think that's born out of metal fans being so obsessive and wanting to know everything about their favorite stuff, getting it on every format, getting every goddamn variant color of a record that gets pressed. There's that insatiability, that true obsessive nature that is what at the end of the day, I think just propels it all forward.

Anthony: Yeah, and most likely keeps it afloat.

Albert: Yeah.

Anthony: You were even, just to refer to something that you were saying in the midst of that rant earlier about some bands having that super clean ultra-produced sound. I mean, maybe this is just my perception more from the outside, but it would seem that... Obviously, bands like that still exist, but in recent years, there's been newer records and newer groups that I feel like almost in reaction to that either are going super noisy, super brutal, super back to basics to the point where they're sounding straight up like a '90s death metal record, or some of those progressive bands, be it like, Horrendous, or Krallice, who's embraced more death metal esthetics recently, or Portal, who you also mentioned in the book. Obviously, they have very technical and progressive elements to their music, but they implement them in ways that just make their songs just so noisy as hell and just so difficult to listen to. And it seems like the technicality has come full circle in a way to where, no, now we need to use it to sound less clean, less precise, and just more chaotic.

Albert: I mean, even you mentioned earlier, Imperial Triumphant has some elements of that where it's obviously insanely technically proficient, but it creates a dissonance with what they're doing that provides the extremity in every element of it. And I think you can be super technical and not be heavy at all. I guess it's also what you're looking for out of that genre. What's the core of it that is motivating your interest? Is it just extremity and brutality? Is it something that's just over the top in a technical way? I think everybody gets something different out of that genre or can take, at times, different things and process them and apply it to what they like about the music. So, yeah, it's all there, man. And it's just so funny how it's all developed when you just go back and what we talked about at the start of this conversation. if you went back and listened to those Mantis demos, and just fast forward 40 years to see where that genre ended up. It's just super wild.

Anthony: Again, everybody, just to remind you, the book is Choosing Death. It's out. It's been out. It's been out for decades now at this point. One of my favorite music reads of all time. A very important read if you want to get into death metal, get into grindcore, extreme metal in general. Writer Albert Mudrian. For coming through and taking the time and just diving more into this and just giving us more insight into all of it.

Albert: My pleasure. Thank you for having me, Anthony.

What do you think?

Show comments / Leave a comment