On April 1, Jerskin Fendrix broke five years of silence on his experimental solo work with a surprise release of a song. No piano and violin — staples in his scoring work for films Poor Things and Kinds Of Kindness — and no electronic pop production from the Winterreise days either. Just a chaotic, brass band accompanying a rap breakdown, a surprisingly catchy acrostic of his name, and a banner that read, "JERSKIN 2025."

Whatever this new project was going to become, it was going to mark a stark pivot in the artist's career.

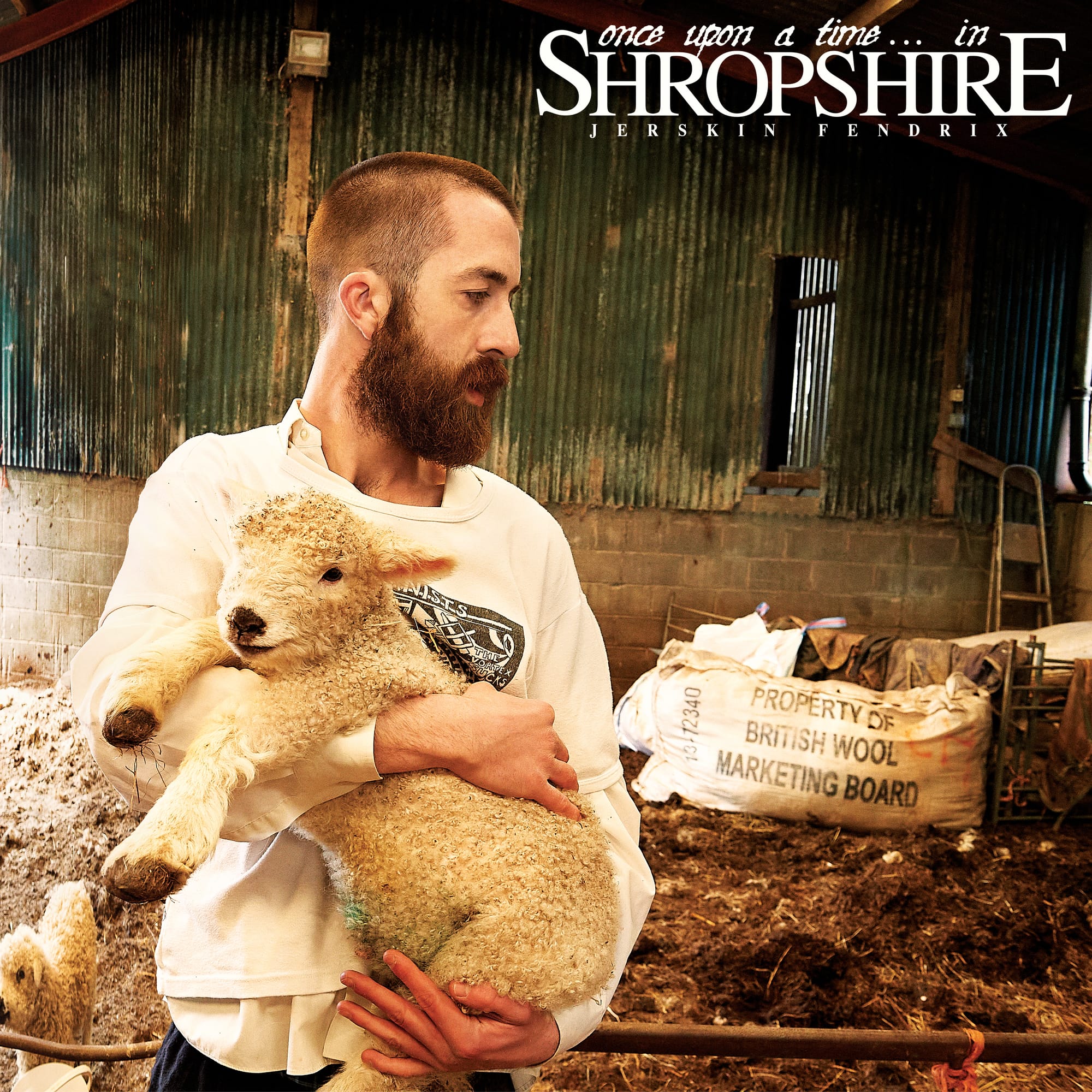

Once Upon A Time...In Shropshire is out today via untitled (records). It's clear that this record is nothing like Winterreise, even if there are bursts of electronica in a handful of songs. (His lyrical humor is still intact as well, which, for fans of "Onigiri" and "A Star Is Born", is comforting.) In fact, Shropshire strips back Fendrix's sound completely, returning to his roots as a modern classical composer with its celebration of raw vocals, piano, and violin.

Initially described as "Ten folk songs about life and death in the countryside," the record is a story within a story. On the outside, there is Shropshire, a timeless and quaint farm town that, for a blip in its ancient history, became the home of the artist. It is sheep, bees, rabbits, grass, and gardens – a hotbed for life and inspiration. Yet, inside lies a folksy melodrama of death, how it came quickly and suddenly to the people living there.

In August, I met with Fendrix to discuss the making of his sophomore record — how the time in between albums allowed his story to "grow organically," how Oscar-winning director Yorgos Lanthimos and his Windmill contemporaries black midi helped to build his world visually and musically, and how he decided to leave behind the production quirks of Winterreise to focus on a more personal story.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Victoria @ TND: It took five years between your first album Winterreise and Shropshire, and in between you also did three scoring projects for Yorgos Lanthimos’s latest films. How was your experience balancing the second album with all that, and how did those projects influence the songwriting and composition of Shropshire?

Jerskin Fendrix: It took long because I started some ideas with the second record, and then Yorgos came along and asked me to do the first film we did together [Poor Things]. That basically sunk my time into a black hole for a bit. Between one and two years, it was a whole process — which was a really good thing. And then…well yeah, I'm a very slow writer, and I really appreciate having a very big amount of time in the middle of projects to forget about it and then come back. It's a very easy way to edit: when you haven't heard something for about eight months, you listen to it, and you can fairly quickly tell if it's like, completely shit or not. It's easy to do it that way, but you don't always have the luxury of doing that. Poor Things was great, however, because I had about two years to get that done. I think if it was a normal, you know, three- or four-month scoring process, I would have totally fucked it. So, I was really lucky.

This all means that [Shropshire] could grow very slowly and organically. By coincidence, the themes I was starting to write about — which are generally fairly either nostalgic or, more actually, morbid — ended up being more about the events over those years anyway. I already had the structure where I was trying to look through some kind of lens of these themes, so I kept writing more stuff about it in the same line.

It's cool how you let the music take the perspective of multiple people, sometimes changing voice within the song itself. When you were writing about the other people and their experiences, what kind of perspective were you gaining from trying to write through their voices and not just your own?

I was very wary of not trying to speak for anyone else. A lot of these events were shared amongst a group of people, so you don't want to trample anyone else's perspective and insert yourself in it. People process things in different ways, and it just happens to be the case that if you are making art, you have a certain way of processing it that can end up being very public. So, the best I could hope for is some kind of testament without making it too glossy or anodyne. I wanted the album to be something that could, to some extent, be shared with my friends, my family, and people who are associated with this place and events. But I did want to be sensitive about it.

I chatted to one of my friends, and she said (which I agreed) that I shouldn't hold back on anything. Having something very difficult or explicit is probably a better testament than, you know, the normal way people tend to write about death, which is usually a two-dimensional… Which that’s fine, and it’s important that people have to do that, but I didn't think that's what I wanted to do with this. I really wanted to dig into the hairier parts of it.

Your album uses death to frame your hometown and thus gets really dark and slow by the end, but its beginning has such a light and full-of-life quality. Like, “Beth’s Farm” has you going to the farm and playing with little sheep and seeing loved ones. How did you decide to use folk and orchestral music to contribute to the themes of death, life, and the community at the heart of the story?

I didn't want it just to be this purity/morbidity thing. I really wanted to cover a lot of what my upbringing and adolescence was like. I mean, in a lot of ways, it's a very human drama, and then the other side of it covers the nature of Shropshire. That place is like… I don't know… it's English Wisconsin. It's boring, it's rural — there's literally nothing. Especially when I was younger, I was really connected to the natural aspect of it, these really old forests and hills and everything. Like, there's something a bit redeeming about this non-unique human drama in a very short time period happening in this place that you feel like is of an age. It doesn't feel like a young city at all.

The album, I think, gives a good perspective on having this big, ancient natural landscape and, by contrast, this very finite thing going on. Some of the composition, I think, tries to be wide-screened with that and capture that part of it as well, rather than just being a personal drama. I wanted to talk about the whole thing; neither part made sense without the context of the other. The very innocent, sweet, young start still has this uneasy tinge to it, and then when you get to the actual dark parts, it’s important that it’s a bit stupid. It's not just like, “Oh, everything was really nice, and then everything was really bad.” There's no reason that childhood can't be sad and despair can't be funny because that's how life actually goes. It's always a balance.

Yeah, one of these guys… I believe it was Samuel Beckett who said the difference between comedy and tragedy is a very fine line, or something like that.

Yes! He's fantastic. He's good at writing about death a lot because he realizes that death is basically as complicated and multifaceted as life is because it's based in the same thing. And that's a good approach. It means you don't get bogged down, and it’s not just like crying or whatever. It's a bad media thing when you see someone dies, and the film has a really sad string music, and it's raining outside, and everyone’s crying at the funeral. You go to a funeral in real life, and it’s a bit funnier than that. People are cracking jokes outside; they're laughing, someone doesn't want to be there, someone else doesn't really give a shit, you know? I've spoken to people about various things, and like, the main thing that comes up is they feel really guilty about not feeling sad enough. Or there’s guilt about not feeling the way they should because it’s “wrong.” That's completely legitimate: songs, films, books, and media say that death has to be really, really one-dimensional. And sometimes it is, but sometimes it isn't. I like the idea of exploring it because there's too much stuff that doesn't. I think that makes people feel bad when someone actually does die.

Comparing Shropshire to Winterreise, I noticed that the biggest difference from a sound standpoint is the vocal work. What I found really interesting about Winterreise is your use of autotune, either aggressively like in “Onigiri” or a bit subtler like in “Manhattan”. This new album is the extreme opposite, relying mainly on your natural voice. I was wondering if autotune played into a theme for the first record, and what purpose the raw vocals have in delivering the performances on this one.

Yeah, autotune is a weird thing. I think it was very in line with a certain aesthetic, which, at the time, I was trying to rip off or parody. It was very 2020.

Oh yeah, “Onigiri” is like, peak 2020.

You know what I would have loved to hear? Brat by Charli xcx, no autotune. It was a good album, but imagine if she had done it raw.

Anyway, for the past decade, there were all these new, exciting vocal effects people were fucking with: Kanye, Bon Iver, and whoever else was there. There were also lots of cool new synth stuff, and there were basically a lot of exciting noises happening. At some point in the last five to six years, we reached saturation. I think we've gone past the point where you could be surprised by a new synthesizer or vocal effect; it's kind of like the kids online basically plowed the entire field…which, sure, that's fucking sick. Like, basically since SOPHIE, maybe just there's not that much new stuff there. So, you've got to find a different way of going towards that.

I struggle to think of a great example, but a lot of weird internet TikTok rappers are singing with no autotune whatsoever and just doing really odd stuff. Like Yuno Miles. Weird fucking dude. He's doing a vocal thing that's incredible — well okay, it's embarassing — but if he were doing this six years ago, he would have just gone into a different thing. But with the permission people have now to use their vocals, I think it's really exciting.

I think actually vocal effects are nice, but they become retro. They might actually start sounding like 80s synths, or 80s snare drums — very much a technology popular at the time. But with regular vocals, there's no aging. I wanted to have something that didn't feel like it was assigned to a time period. And with some exceptions, I do think that I can probably achieve a bit more emotional honesty using my real voice. I liked [using autotune] for “Onigiri” because it made me sound like a dumb fucking kid, and I think how embarrassing I sounded on that was really important. I didn't want it to be like, “Oh, I've had a breakup!” I wanted to sound like a fucking idiot and be as honest and embarrassing with my position as I could be. Otherwise, it would be self-aggrandizing. I try and do all the falsetto stuff on the Shropshire thing, and like, my voice is through the fucking pavement. So, when I try to sing that high, it makes me sound like a fucking idiot as well.

It's important that I don't sound cool at any point. I really don't want to sound like… sexy, or stylish, or badass about anything. Like, if I can be honest, I like to sound as dumb as possible all the time.

Why?

It’s a defense mechanism.

To be fair, a lot of people use autotune as a defense mechanism. To use your example, I’d like to hear a raw version of “I might say something stupid” because it’s Charli’s most vulnerable song, but the autotune puts up a wall of sorts.

Exactly. Autotune is a big [defense mechanism], as well as general wacky effects. But there are interesting exceptions. There’s bit in Kanye’s My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy song “Devil in a New Dress” where he starts doing a really distorted thing, and no one had ever done that before. And it's like, “Oh shit! That was somehow very sincere.” And there's a big thing within electronic music, which SOPHIE was part of, where the context behind vocal and pitch-shifting stuff makes a lot of sense, and actually that's like a very, very interesting way to use something that people have used before.

But generally, I think you can be really weird with the voice without drowning it in stuff.

Did playing with the range of your vocals and seeing how they could be as strange as possible on their own help, to an extent, create the voices of the people that you were trying to channel in Shropshire?

It's a good question. In “Princess” I'm basically speaking from the point of view of a woman, and I'm not singing massively high on that. There's a song called "Mum and Dad” where I'm [lyrically] switching between my dad and my mum, but again, I'm singing in a pretty low register for most of that. The different voices were probably a consideration at some point, but I think it became strictly lyrical by the end. Otherwise, I think it starts being a bit too pantomime-y potentially.

I also don't have a gorgeous voice, so I'm working with what I have. I don't have a Bruno Mars-y, Benson Boone situation going on. It'd be lovely and great, but that’s just not happening.

You did say before that the hardest part of the album was recording the vocal parts and doing all the takes for them.

The most brutal part was basically the last three or four months of writing it. There were a lot of moments when I wanted to look at Shropshire and redo it. Trying to capture a place during certain events that very personal and known to only a small group of people and in a very niche context — not diluting them so much that they become meaningless, but not being so specific that it's just an in-joke — that was hard to do. In the same period of writing and finishing, I thought I was just going to have the demo vocals for everything recorded properly. But that was when everything was still quite raw.

The singing part was difficult, and it was just emotionally very, very taxing. It somehow became a very punishing thing to do for myself. It was very sad to realize that it was just me in a studio by myself for the whole album. I tried to do [the vocals] properly later and realized that like, despite the unpleasantness of that, it was the right time to do it. And then… you know when you're comping the takes, and you have to take the time to go back and go through them all? I was just regularly stopping to cry. It was a form of processing things, and I think that it's lucky that I could go through it properly.

I don't think a lot of people have the work or time where they're able to spend that long withering in their own fucking misery. It was tough. I was very, very hard on myself, and I get angry at myself for getting things wrong even though I wasn't even getting to the part where I get things wrong. But, I’m glad I did it.

Back to the music in Shropshire, there are lot of orchestral sections in the record overall, including a big band in “Jerskin Fendrix Freestyle”. Who did you work with to compose the instrumentals? How was the process of designing the parts of Shropshire that aren’t either the piano, the violin, or the other instruments you would normally play?

The film scoring experience was really great; before it, I think my writing lens was a bit more constrained. Poor Things forced me to see what my music might be like in a larger context, granting me permission, in a way, to be grander with the album. The first part of the record was written during the pandemic, and I started writing Poor Things while the pandemic still happening. It was this odd moment where I knew something very big was happening, but I hadn't been to the cinema in a year (and couldn’t go for another), so I was very caged in. I guess the film was where I kind of blew that all up a bit, so that was really helpful. I think that has really been positive on the album.

I got all the members of black midi at various points to do a lot of the recording. Morgan [Simpson] played all the drum parts, which is very kind of him because he's the world's best drummer. I was really lucky to get him. Cam [Picton] did a lot of the bass guitar and some acoustic guitar as well. He’s another one of the best; he's really fucking good. Lastly, I got Geordie [Greep] on “Jerskin Fendrix Freestyle”, which is basically a song we did together, and I just told him to go fucking nuts on it. That was the song with the most musicians: Geordie, a bunch of brass players, Morgan, and more. The band stuff is more where I had to ask people to help.

The strings are mainly just me overdubbing the violin, which is the same thing I did for Poor Things, so I don't technically have a section for that. I just do them myself because I have a certain way of playing the violin, which is kind of a bit wrong, so it's cheaper and easier to do that than get a naturally great string section to, you know…imitate me. I think in a lot of ways, Poor Things is everywhere in this new record: the orchestration was done similarly, and there was a similar idea of trying to get a lot of dumb and personal stuff to sound like it's grand. But also silly.

Shropshire has a surrealist edge to it in the same way. Like, my favorite bit in “Beth's Farm” are the syncopated, slightly unnatural choral arrangements at the very beginning.

Fun secret: those are all vocal synths [using Logic Pro X]. They're not real people. I use those all the time. I feel like I use them quite a lot; they're great.

So “Jerskin Fendrix Freestyle”. I have thoughts. And questions.

Many of my closest friends do.

It was hilarious to surprise-drop it on April 1st with no explanation.

Oh yeah! That was my label’s idea; I loved it.

How did you come to the conclusion, “This is the kind of sound I want. This is an utterly ridiculous song I want to put in the middle of my album”?

It’s the dumbest thing you could put in between “Mum & Dad” and “The Universe”, which are very sincere songs. If I were to have a decision-making matrix in front of me, it would basically be, “What's the dumbest possible thing you can do at this juncture?” And then I always make sure to do that rather than the less dumb thing.

Lyrically, it's a good summary [of Shropshire], which is why I was happy to share it first. And yeah, sure it was an April Fool’s joke — the song itself is kind of a joke — but I also take making jokes very fucking seriously. The lyrics cover basically every part of what's even on the album. They cover being an adolescent, debts, being angry or scared about death. They probably covered betrayal more than anything else in the album. It's very dense: more of the tough-to-swallow truths are in that song, and they're covered up with the instrumentation that sounds nuts. All the players are doing great stuff, and there are very fast bass and drum parts to make it nicer. But it's a very, very sad song, if that makes sense.

Yeah, I mean to me, it’s a song that just feels like you’re constantly slapping yourself across the face.

That's a pretty good description, yeah.

How did the band and Geordie come together to help design that big, crazy sound?

I basically had opposite power. Because at that point of my music recording career, I was recording every instrument separately. (Basically, I record, pitch, hit ‘Shift + E’, and shit like that.) So we had drums, one sax player, and one trumpet player, and that was kind of it; we just played them over and over and over again. They had a very set rhythmic thing they had to do, but notes-wise, I just let the band do whatever they wanted. I ended up with a stack of 20-part harmonies of little things.

And then Geordie comes in, listens to it once, then starts playing the chords of this random set. I didn’t even know what the chords were, but he goes, “Oh it’s this!” and starts matching every note with a six-string guitar. Like shit, that's how fucking good he is.

Yeah, he's one of those artists I see every single time he comes to NYC. I love it because I have no idea what he's going to do ever. He'll take his already amazing record and just turn it into something crazier.

He's got the amount of nuttiness that you get with a lot of weird London personalities’ music, and he knows more about any kind of music than anyone.

For some of the longer tracks at the end like “The Universe”, “Last Night In Shropshire”, and “Together Again”, how did you approach the natural flow of things while making sure that you say what you have to say without losing meaning?

I wasn't performing live while I was making Shropshire. When you perform live, it's sort of like standup, where you can test out the material to see what is or isn’t landing. I think I did that a lot with the first album — which basically got made while I was performing it — so it's quite tight. The momentum's pretty good on Winterreise. This one's a lot slower and more contemplative, especially towards the second half. I knew I wanted to have shorter and poppier stuff for the younger part of the album. For the second half, I really had to not care massively how it was going to go down emotionally. I wanted the space for it to be difficult, to stop time and not click, which is quite hard to do when you're layering instruments. And that made it very long.

[“The Universe”] was one of the songs where I was trying to think about the wider landscape painting of space and time. I did want it to sound dumb as well. The thought behind that was, “How many words could I possibly get in before I had to do the high notes?” Songs like “The Universe”, “Together Again”, “Beth's Farm”, “Mum & Dad”, aren’t normal. They’re trying to do a lot of scene-capturing and third-party description; that makes all of them a lot longer.

The editing was fairly brutal. “Together Again” was way longer; we had to spend ages cutting it down. It originally had the most fucking irritating backing track possible; it had this really stupid folk thing... It was so annoying to listen to. I was like, “Fuck, I really need this song, but this is the most irritating thing!” I had already gotten it all recorded, so then I took out the folk thing and just played piano to the vocals in a reactive kind of way, which I'm very glad happened. That was originally the most annoying song of all time, and now it's not! It's now only one of the most.

Coincidentally, “Together Again” is one of my favorites because of that twinkling piano. And I do have to admit, the line, “There's a bee in my coffee / And a song in my heart!” is always stuck in my head. I don't know what makes it so catchy, but also… real.

Yeah. It's a true thing that happened! Well, I don't think there's anything on the record that's technically untrue. It’s dumb crap that becomes my favorite thing to write about, which are cute animals. I love writing about cute animals. That's more way more fun to write about than anything else. Most rabbit references are in that song, I think.

I imagine the photoshoots with the Shropshire sheep were very fun! They were so cute.

They were fun! They were weird. Sheep headbutt sometimes. Just out of shot in the photo of me holding the lamb, its mother was at my legs just bashing me the whole time until I put it down.

They all starred in “Beth's Farm” as well.

Speaking of “Beth’s Farm”, the music video was directed by Yorgos Lanthimos. When it came to scripting that, how did you work together to create a weird little surrealist world?

We didn't, which was great! It has been the best.

When you're a little DIY person, you think you're good at stuff, but you're not. Artists in London try to be a control freak and think about everything. You do all the artwork; you sit with the mixer in all the sessions — you try and do everything. Then, as soon as I started working with Yorgos, I got one of the best bits of education from him. He picks people he really likes: actors, writers, designers, people he can trust. And he just goes, “Do it.” He doesn't want to know how they come up with the idea; he will actually tell you to be quiet if you try and explain your concept like, “Oh, I did this because of this!” He wants to be an objective audience. He’ll put a lot of effort into picking someone, but once he gives orders and sees our work, he'll say yes or no. It's a great way of delegating a lot of creative people while driving the whole thing.

For Poor Things, I assumed with a big-boy director, we’d talk about [my score] and develop it, so I just sent him a bunch of demos. And they were demos. He was like, “Alright, cool! That's in the film. What else have you got?” I was like, “Oh fuck, I would have worked way harder on that! I didn’t know that that was going to be it.” Those are still in the film, and I didn't get to change them. From then on, I learned that you have to make decisions because no one else can make them for you. You have to be very responsible and work way harder, and it makes you better at editing and doing the right thing. You can't give people options or something half-done.

So, I extended the same courtesy to Yorgos. I showed him the album, and he was very sweet about it, as was Emma [Stone, who’s in the video]. He brought up the idea to do a music video for “Beth’s Farm”, and I was like, “Okay, well, let's do it!” I didn't do anything with it from that point; I turned up on the day of filming. So now I can be very proud of it and say it's amazing because I had nothing to do with it. I just fucking turned up! I think it's a beautiful story. It's got really good symbolism of how one cares for someone, what death means, what commitment means, and also what artistic self-flagellation means. They're very fucking good. It's very fucking good.

Is there anything else about the record that you've wanted to share?

I've been thinking recently about the stuff that I'm doing, and how fragmented it is. I think that it was an excuse to do a very rich and broad tapestry of stuff in one album — having “Sk1”, “Sk2”, and “Jerskin Fendrix Freestyle” represented these different facets of it. If I grew slightly older and slightly more mature (but only slightly!) I wonder if there'd be a version of the album that basically takes those three out. If it was someone else's, I might have done that, but as it stands, it's a good testament. But also… you know when you do deluxe releases and there are more songs on it? I thought a deluxe release with fewer songs would be a really good idea, or at least a funny one…

I guess I've never understood people who are really good at committing to a genre. I don't want to be an experimental artist. I don't try to do it; it just happens. I do want my music to be accessible. I don't want it to try do big stuff for the sake of it; I want it to be natural, to be intelligible to people, to mean something emotionally. I'm really glad about the music videos because I think they helped translate it better than I can. I think if the album seems at least a bit incomprehensible — which it probably is — I think the videos do help with it.

Once Upon A Time...In Shropshire by Jerskin Fendrix is out now via untitled (records).

What do you think?

Show comments / Leave a comment