"Home to you / Is a neighborhood in the night kitchen," Welsh artist and songwriter Cate Le Bon once exclaimed in a song. As we connect over Zoom, Le Bon is in the midst of refurbishing a familiar kitchen in West Wales. While her parents are away, she's is painting the walls and ceilings anew. She apologizes for not turning on her camera, for she herself is apparently covered head-to-toe in paint.

The situation triggers a memory from Le Bon's salad days. Though memory has often proven itself an unreliable agent as years tick by, this particular one of accidental mischief at this house remains relatively unspoiled:

“I think I was about twelve," Le Bon recalls. "My older sister, who was fourteen, persuaded me to paint the stairs and landing while our parents were at work. She figured we could do it in a day. You know, when you’re a kid you have no concept of time. Our parents came home and we’d maybe done about four square meters of a terrible paint job. We’d slapped some horrible blue gloss on the wood on the stairs, and they obviously went nuts. We painted over everything: dog hair, crumbs, human hair. It was shocking. But we were twelve and fourteen."

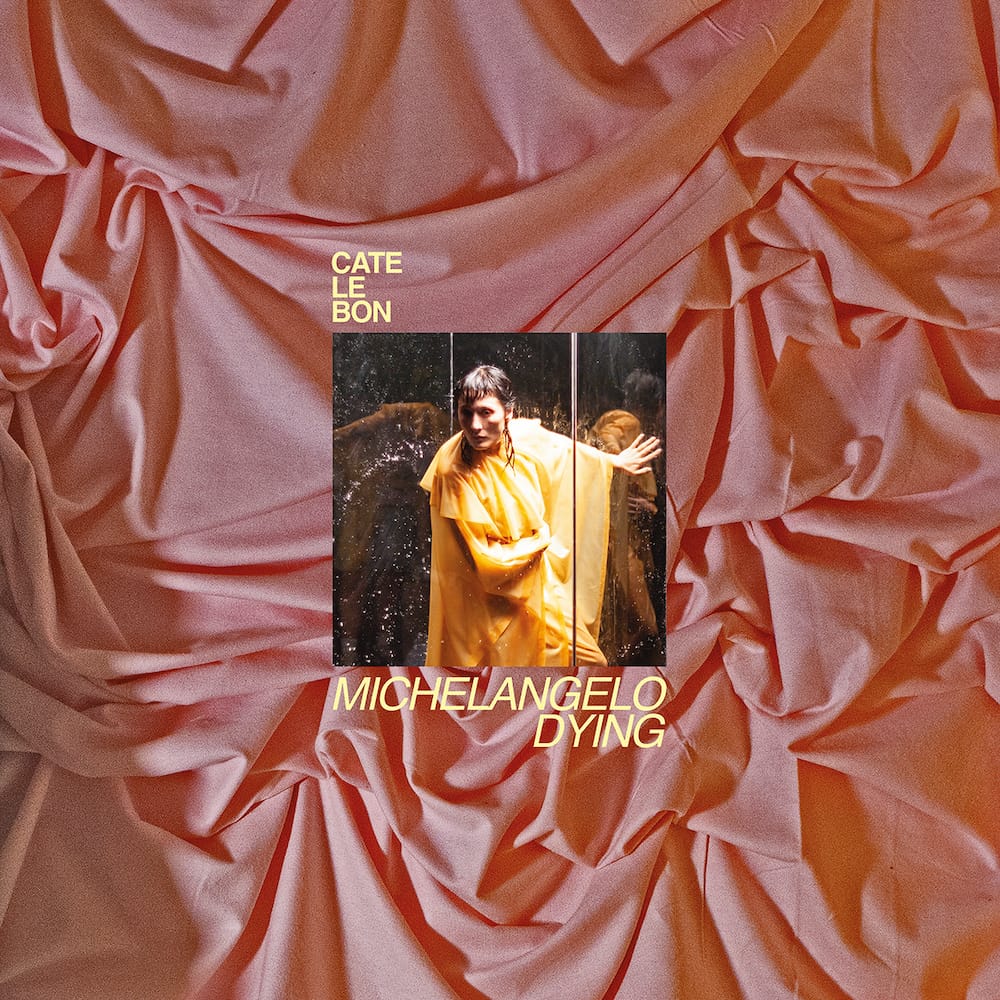

Three decades later, Le Bon shares a short video on Instagram with her co-producer Samur Khouja. She is somewhere more otherworldly, on the Greek island of Hydra on the first day of recording her new studio album Michelangelo Dying, amidst flooded stairs. Was it a bizarre Biblical premonition? Or just a lucid dream?

In any case, Michelangelo Dying deals with a different kind of shock: the healing from of a longtime relationship coming to an end. Though the geometry of Le Bon's fragmented avant-folk and post-punk has been a potent vessel for conveying life's strange motions, the spectre of heartache isn't swayed by a simple paint job. It rearranges and scrambles everything attached to it, crumbling the foundations of one's very existence.

Le Bon, who also builds pieces of furniture, would know a thing or two about that. She has recently taken up boxing, which requires rolling with the punches, and adopted a rescue dog, Mila, to incite care and companionship. Hence, the heartache on Michelangelo Dying doesn't sound dark and defeatist, but remarkably malleable, inquisitive and translucent. "This is how you break a leg / You let the shadow lead the shape," she sings on "Pieces Of My Heart".

Coincidentally, a good way to begin a conversation as well: one predominantly about different forms of grief and how they never really end – they only change shape over time.

This Q&A has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Jasper Willems @ TND: I heard you have adopted a dog and have taken up boxing lessons. How's that been?

Cate Le Bon: The boxing was good, but I’ve had to stop: I’ve been too busy traveling. But the dog remains, obviously; I’d never give her away. She’s wonderful. It’s lovely to have a little soul following you around. She sleeps in the bed with me. She’s a really sweet little thing.

Are you happy to be back home again? I reckon, in the wake of all your traveling, performing, and human-encountering, life outside of home might slowly start to feel like some sort of distant dream.

Yeah, it can. It’s been really lovely resting and spending time with family and close friends. I think I struggle to feel like I’m where I should be, which is why I’m constantly moving. I do have a hankering to try living somewhere else again. But we’ll see. Mostly, I feel rested for the first time in a long time and connected to myself. Mila, the little dog, helps with that. Sometimes I feel like I need permission to be fully present somewhere, and getting a little dog certainly does that. But still, there are lots of places I’d like to try living, too. I don’t know. Maybe it’s just a perpetual chase I’ll never win.

Are you moving around this familiar environment differently now as opposed to when you were growing up here?

It’s hard to say. I’d been coming back to Cardiff quite a lot, and to where I am now in West Wales, where I’m from. A lot’s happened. The pandemic shifted so much for me – it was a horrendous time, but it also gave you permission to be where you were, to let go of the responsibilities of life as we knew it, to surrender to the conditions we were all under. A lot came from that: seeing and experiencing things differently.

In Cardiff I fell in love with the big park I’d only ever used as a shortcut from one side of town to the other; I started going there just to spend time. And back home, where it’s quite rural, all those roads that were just routes to somewhere else became destinations. I spent a lot of time running them. There’s a metaphor in there somewhere, I just can’t be bothered to find it.

I've found out I'm exactly 2 days older than you. For some reason, this fact compels me to ask you about impactful musical memories back in the 80's. Mine was hearing "Shout" by Tears For Fears and the video for "Loverboy" by Billy Ocean.

Growing up, I was a massive Kylie Minogue fan. When her videos came on TV, back when glimpses of your idols were rare, it was, ‘Ah, Kylie in a music video! She’s amazing.’ But musically, she wasn’t a big influence. My dad was the real music obsessive. I grew up on his collection — the mixtapes he made for our holidays. Those are the soundtrack to my childhood: lots of Neil Young, Steely Dan, and Crowded House. Then, when I was thirteen, he introduced me to Pavement, which was huge for me. It felt like the first time I heard music that was truly mine, resonating in a way I’d never felt before. So, at the start, everything was funneled through my dad.

Sweet. I also read you liked "My Sharona" by The Knack for a brief period.

Well, at the time, yeah. But it hasn’t really stayed with me. It’s not a song that’s stayed with me, but I remember hearing it, and that was the first time I remember standing in front of the patio doors at night, watching my reflection and playing a Telecaster to “My Sharona”. It was on a compilation CD that my dad had rented from the library in Carmarthen, and I played it over and over for a long time.

I can't help but think about your friend Bradford Cox, who played with Atlas Sound and did that song for a whole hour on stage. I wonder if you’ve ever done something like that on stage — this big ad hoc thing that you didn’t plan.

I don’t think so. All the songs in the set so far, recently, have been very meticulously planned, so there’s not much room to go off-piste in that way. But yeah, it’s the kind of thing only Bradford can get away with, you know? He’s got the charisma to play any song for hours and hours and still make it feel urgent and new.

It's kind of a lovesick song about a girl. I wonder if the singer of The Knack still misses her, because that song is so ubiquitous. Every time he hears it, he has to think about Sharona again. Otherwise he'd forget, right? It sounds kind of like a pickle.

But a pickle that means he’s driving around in a really nice car listening to it. Or perhaps the perpetual heartache is the cost?

Which brings me to your new record Michelangelo Dying. The imagery is beautiful — on the sleeve and in the video for "Heaven Is No Feeling". I’ve always thought of you as an artist who doesn’t create with an audience in mind, so seeing you in a video where you seem to watch yourself drown really struck me. How did that concept originate?

Making this record was very private. I was single-minded and completely absorbed by it. It never felt like a product; I didn’t even think I’d finish it. It was a constant emotional outlet, a way to experience and heal from a heartache that had consumed me. Heartache is a strange neurosis; it keeps you in loops. Fractured memories catch you off guard, and it’s disorienting. Experiencing that through music — which I’m obsessive about — only deepened the obsession. There was no end in sight.

When I finally did finish it, much to everyone’s surprise, I stepped back and began to experience it from the outside. On the record, I thought I was singing to different characters, maybe… But once I stepped out of it, I realized I was often singing to myself, or seeing myself through someone else’s eyes. You catch yourself through a different lens — a mirror or window you’ve built for yourself. That’s what I wanted the music video to reflect.

It’s beautifully directed. The room full of pink clothes, I've heard it was inspired by an installation. But it made me think of an interview I once did with Haley Fohr (Circuit des Yeux). She had her room draped in orange clothes as she processed a different grief, the death of a friend. It’s powerful to see someone make emotion tangible like that. At the same time, it can feel like that’s what people expect artists to do, which can be burdensome – ‘I’m an artist; I have to do something with this – or not." Did you feel that tension too, especially since this heartbreak felt new again?

Honestly, I didn’t want to make a breakup record — it felt like a cliché. But it was inescapable, and, in the end, necessary. You can try to sidestep heartache, but you’re really just carrying it around. So I surrendered and stared it down. Visually, Colette Lumiere’s installation Real Dream hit me hard. I didn’t understand why at first — it was just another piece of the puzzle of how I felt.

Being able to show it to Samur [Khouja], my co-producer and dear friend, mattered. With him, I feel like I can be ‘together alone.’ I could say, ‘I want the record to sound the way this feels,’ and he understood. All of it came from necessity: trying to build a world that’s like describing a dream – you can almost get there, but it stays just out of reach. That’s how records appear to me: they have presence, form, and color, but they’re ultimately a feeling. I need to get that feeling out and shape it into something that matches what I’m living. And when that something is love, one word for a feeling with so many faces, that’s where it gets tricky.

It’s a different, bigger emotion. On Mug Museum, the grief was of another kind, someone older who left things behind. Grieving death is different from grieving love. How did those different types of grief manifest for you?

It is different. My grandmother was old, and that record was more about how her death shifted the familial line. And how it made me think about myself, alongside the grief of losing someone and what’s left behind. But in this situation, the grief is that love isn’t enough. That, to me, is the saddest part. It’s complicated and harder to grieve, because nothing has died; things have shifted. That can be hard to get your head around.

Heartbreak can feel unreal. When my mom died, her belongings gave grief a place and shape. With heartbreak, nothing physical remains; it sits inside and you wonder where to put it. I’m not an artist — I can’t transform it. [With regards to the production] on Pompeii, the bass was the connective tissue. This new record sounds lush, soft, and reverby — did certain instruments carry specific meanings?

Yeah, it came together in a very different way. With this record, everything seemed to form at once. There was a lot of scrambling — between guitar, piano, synth, and bass — just trying to find what resonated with the feeling. It was a bit all over the place, but in a way that was necessary. I relied on instinct, trusting whatever felt right, even if it was unorthodox, even if it meant starting a song in an unusual way. And Samur really pushed me out of my comfort zone, into the discomfort of leaning into the emotions instead of trying to mask them.

Coupled with that installation, that was the beginning of me saying, ‘I want the record to sound like this,’ and of us both understanding what that meant. It’s a map of sorts, but not a confining one. It’s open to interpretation. It’s the beginning of the conversation rather than the whole transcript. So there was a lot of instinct and trust that the world we were building truly resonated with the lyrics forming at the same time, and with all the emotions.

And the emotions were constantly changing, too. It was quite a movable feast for a long time; everything was in motion. Songs went through three or four iterations before I felt ready to let them be. It was a very involved process that stayed in motion for most of the time we worked on it.

How did your production work with others artists — namely Horsegirl, Wilco, Deerhunter, St. Vincent — shape this record? Making an album is intense, professionally and emotionally. Did watching them navigate their own processes spark any revelations or inspire you to try new approaches? Did those collaborations expand your universe and help you level up in ways you wouldn’t have otherwise?

I’m not sure I can point to specifics, but I’ve worked with incredible people over the last ten years. In the studio, it’s about being porous and listening — being completely honest without assuming honesty makes you ‘right.’ Letting go of the idea that anyone is right or wrong is key.

Spending time in the studio with Jeff Tweedy taught me so much about music — and about life, love, and loyalty. All of that funnels into your creative work. Horsegirl blew me away: their level of communication was incredible, the way they spoke to and respected one another, making sure everyone felt heard. That was deeply inspiring.

Annie [Clark, of St. Vincent] is brilliant at asking restorative rather than reductive questions; that’s something to be mindful of. And Bradford [Cox] compressed twenty years of experience into two months. He taught me to feel entitled to my work — not in an egotistical way, but in the way I needed as a young woman in the music industry: how to occupy the space that’s mine so no one else occupies it. That was hugely important and valuable.

Despite of Michelangelo Dying being your heartbreak record, you still manage to be incredibly funny. On "Body as a River", you sing: "I made the panic of impermanence matter", a line which I myself would not be ashamed to have etched into my gravestone. The word "panic" surprised me, though, because – from the outside looking in, at least – you always seem so adept at letting chaos work for you. I also read that you were dealing with physical ailments too. How did you navigate that, and did you let it inform the work in a specific way?”

Actually, it was after — the moment I was about to announce the record, I realized I didn’t have enough in the tank to tour it or even release it. So I took a year to rest and recuperate. I’d reached a point where I just couldn’t do it; I needed to stop, so we delayed the release. Looking back at the song "Body as a River" where I sing about being sick all the time, I was kind of oblivious to the fact that I was becoming ill. It reads now like a strange letter from my past self.

It’s funny how artists sometimes sense things before they happen, like animals sensing a catastrophe long before it hits us. It’s strange, right?

Yeah — and then still being shocked when it happens!

Michelangelo Dying comes out September 26 via Mexican Summer. Preorder here.

What do you think?

Show comments / Leave a comment