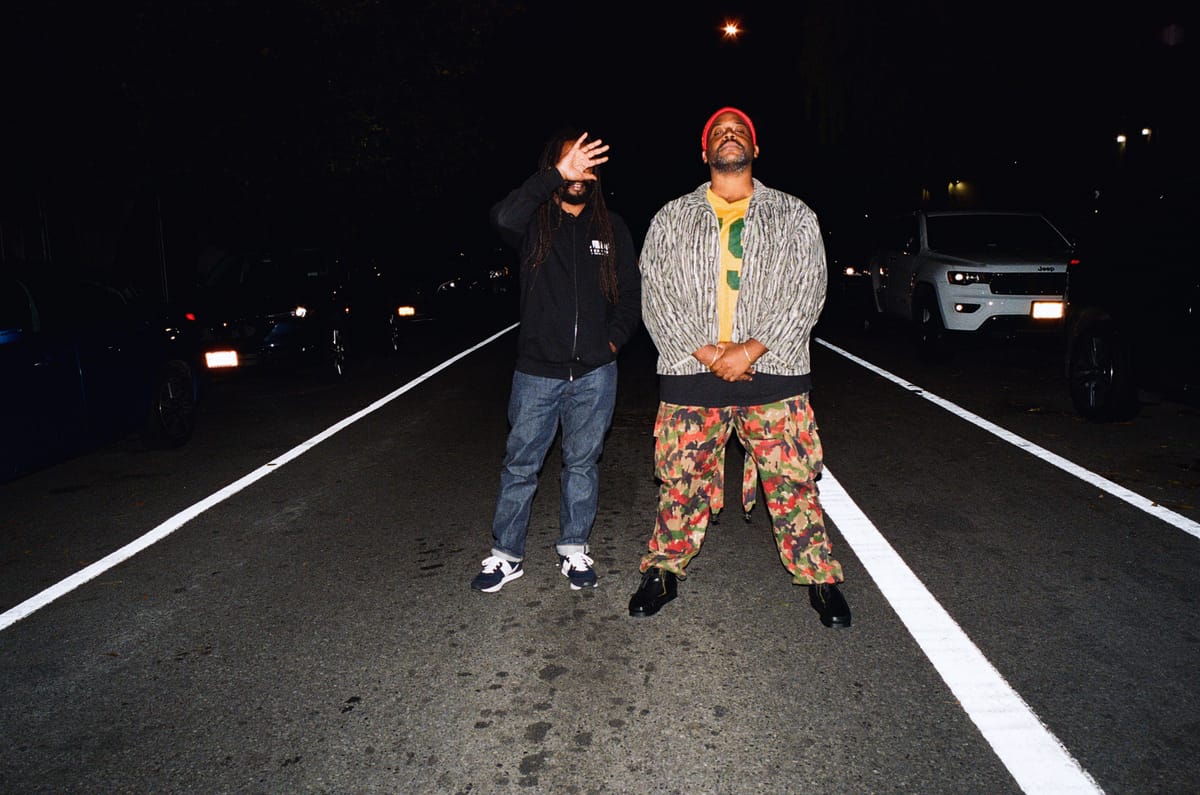

We catch ELUCID and billy woods – the two prolific rappers who together make up Armand Hammer – driving to a location for their next music video. The situation makes up for a sometimes buggy connection, but the duo are gracious and understanding amidst the persistent snafu's during our call.

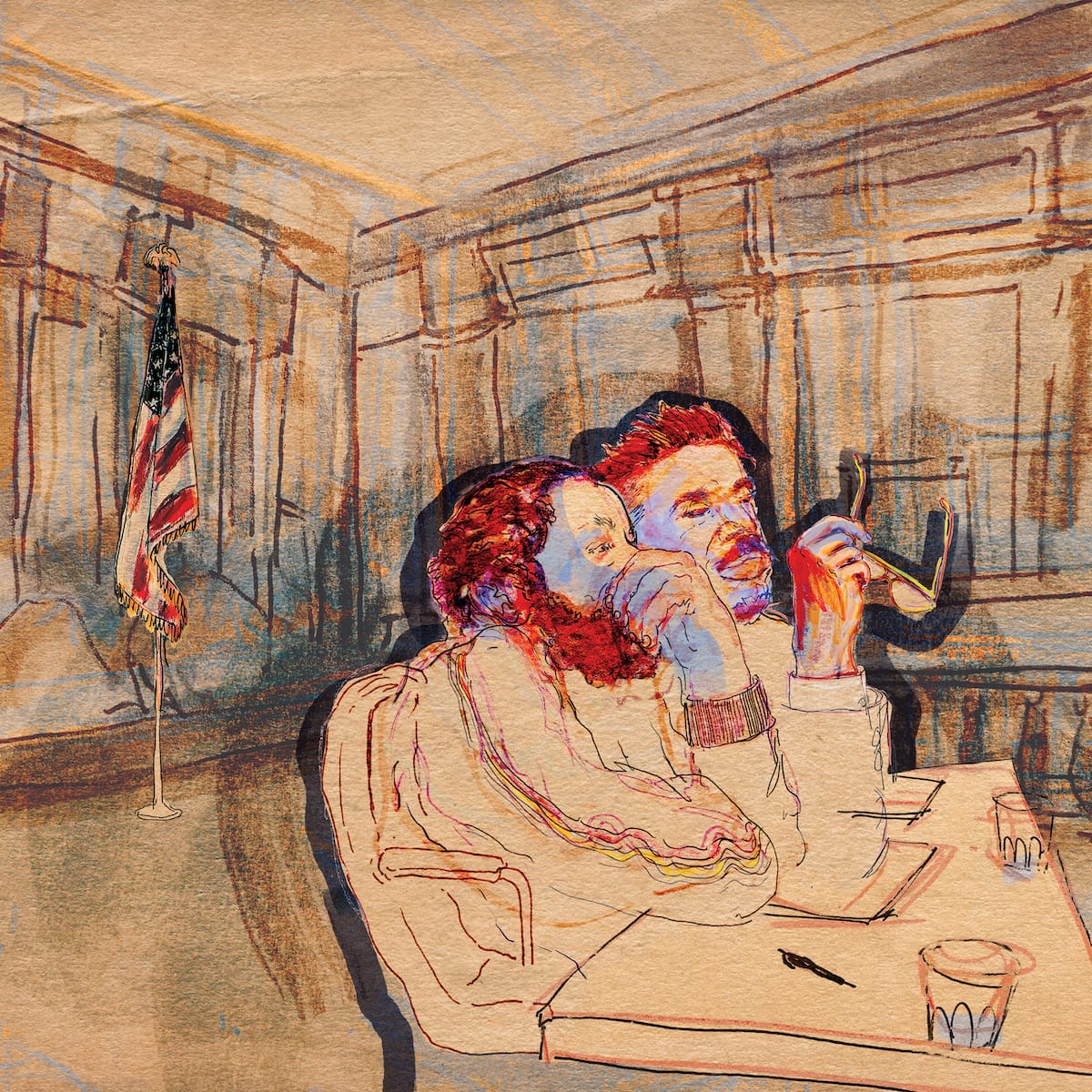

For Armand Hammer's new album Mercy, they once again worked with legendary beatmaker and producer The Alchemist – their first collaboration since 2021's Haram. Though the fruits of this golden collaboration were once again reaped plentiful, the results themselves manifested into an entirely different record – each beat contorted into a monolith for ELUCID and woods' peerless wordplay and production smarts.

On Haram and We Buy Diabetic Test Trips, Armand Hammer channeled a real-world urgency, whereas Mercy sounds more like a cosmic fever dream, gradually drifting from the frantic stop-start punk rock of "Laraaji" (talk about a song title being a red herring), cosmic jazz of "Longjohns" (featuring some spectacular guest vocals by Cleo Reed), and the vintage nostalgic daydreaming of closer "Super Nintendo".

Mercy features an impressive tally of guests, including Reed, Earl Sweatshirt, Quelle Chris, Pink Siifu, Kapwani, and Silka joining in. We were grateful the duo agreed to chat with us about it all.

This interview has been edited and compressed for clarity.

Japster @ TND: What's the overall outline for this video you're shooting today?

ELUCID: We actually did part of it yesterday at Fort Tilden, a beach in Brooklyn. It’s an old military base that’s been left abandoned, so there are some pretty cool, large-scale structures that are really interesting—you wonder what was happening at these particular structures. And today is in the Bronx. I’m not really sure what I’m walking into. Our video guy, Joseph, who’s done a bunch of things with us, is already there, so we’re going to meet him.

For which track is the video?

ELUCID: "Laraaji".

I thought with that one I was going to get some kind of dreamy, Alice Coltrane-type stuff. But instead this track really jumpscares at you.

ELUCID: Yeah, I like some of Laraaji’s music. He’s obviously really legendary. I’ve seen him live a couple of times, and I know a few people who have been meeting him lately—the circles are shrinking. I’ll probably meet Laraaji in 2026—I’m pretty sure.

Janelle Monae recently claimed she travelled back in time to see David Bowie during his Ziggy Stardust-phase. Who would you see if you could travel back in time?

ELUCID: My first thought when you said it was Fela Kuti — that’d be my first one— with Egypt 80, somewhere in Lagos, maybe even in the year of my birth.

What about you, woods?

billy woods: Ah, that’s a tough question. There are a lot of things I’d pick — it depends. Are we talking about going to a show, or getting to be around them and see what they’re doing? If it’s the latter, I might pick Lee Perry when he’s really getting into the Black Ark period and creating dub music. That would obviously be really bugged out — the weed would be flowing. It’d be cool, and I think it’d be a relatively safe situation. It would also be interesting to be in Jamaica at that time — with my family ties and background, there would be lots of layers. If it were just to see a musical performance, then for a similar combination of genuine appreciation, interest, and historical reasons, probably Bob Marley at Rufaro Stadium, 1980.

That one makes a lot of sense.

billy woods: Probably because of all the things in play at that moment — Bob isn’t going to be alive much longer, unbeknownst to him — and the other Bob (Robert Mugabe) is on that stage wondering when this Jamaican guy is going to finish so he can take over. Yeah, that would be my choice: a really interesting historical moment, and one I was only a handful of months away from being there for.

Let's point the appreciation-arrows towards each other, specifically recent solo projects. woods, what's your take on ELUCID's Revelator? And ELUCID, what did you like about GOLLIWOG?

billy woods: Revelator is interesting. To me a lot of ELUCID's work takes place in the Backwoodz universe. We collaborate closely and know a lot of the same people. There are things on Backwoodz Studioz that I’m seeing being built to different degrees, from the inside out. And sometimes he has side projects, like BRB I Gotta Charge My Toothbrush, or working with The Lasso on "Small Bills", where I’m only put onto them when they’re basically done.

The Revelator record happened a little in between. I knew more about where it was going and what was going to happen, and I had a couple of features on it. So it kind of split the difference. I thought it was incredible. Personally, really groundbreaking in a lot of ways, totally different from other things that were out, and continuing in the tradition of a lot of his records: really great, forward-thinking production. You gave it to me and asked what I thought for a sequence, and I was like, ‘Man, this record’s crazy.’

It’s interesting you ask about the two records, because when I got that Revelator, Mercy was on hold at that point – we were probably about 40% through — and it put it all differently for him. He was working on his solo, and I started working on GOLLIWOG just to be doing something. I remember hearing Revelator and thinking, ‘Alright, I’m glad I have more time to work on this record, because my records needs to be a lot better.’ I was like, ‘Wow, this is really crazy. I’ve got to do more. It’s got to be better.’

Something like "Bad Pollen", doing that song on Revelator, led me to connect with that producer (Saint Abdullah, ed.). I asked, ‘Who did this?’ Those producers sent me a bunch of beats. I was in Barcelona at the time, at this weed club, going through the beats, and found the one for "Maquiladoras", a pretty crucial song on there.

It's cool to hear these projects still being connected, despite you two being in your own lanes a bit. ELUCID, how did GOLLIWOG resonate with you?

ELUCID: It’s obviously horror-themed, horror-centric. I’m a fan of horror, and knowing woods — and myself — what I also like in horror is the humor. I feel like [GOLLIWOG] is woods really sharpening that blade; it’s always there, but on this record it’s fully utilized. I think this record is a funny-ass record. As harrowing as some points can be, the black humor is so potent, and that’s what I really love about woods’ style, one of the first things I loved about his style. It’s good to see that branded so heavily there. And with the production, woods has been working with one producer for a couple of records... like, three in a row?

billy woods: Yeah.

ELUCID: It’s really nice to hear him choose an assortment of beats from different producers and get those different tones and frequencies on a record. It’s exciting, in a particular way, when you’re able to work with different producers and choose them well — choose beats that complement a particular style to make a point. I love doing that personally. So yeah, GOLLIWOG was a phenomenal record in that sense.

billy woods: Yeah, it’s connected in other ways, too. The beat that eventually became the Shabaka [Hutchings] and Haram collaboration — parts of that beat we’d had; you’d picked it way back. Remember, she had it titled ‘Great Wall,’ and you’d picked it way back possibly for your record. You floated it to me as something I should write to, but by the time I came around to writing, it had shifted. I don’t know what happened. I still had it on my computer and kept thinking about how to incorporate it, or what we were going to do with it. So that’s another way they’re connected.

Let's talk Mercy, your second album now with The Alchemist after Haram. Was the playbook a little different this time around?

ELUCID: First off, we had a lot more back-and-forth flows, like a classic rap duo. We’re definitely doing that. Working with Alchemist was very similar between this one and the first one: choosing beats, him curating, us being in Los Angeles with him in the studio: listening, choosing, and recording. Both were very similar processes.

billy woods: While our lives were in different places, there were surprisingly few material differences in how we recorded the record, the processes were very similar.”

Let's say Alchemist is like your point guard on this project: which beats on Mercy immediately made you react and flow into your raps, and which beats forced you to labor over them a bit more, get to your spots and into your bag a bit deeper?

ELUCID: As soon as I heard the beat for "Laraaji", I was like, ‘Alright, let’s get serious — really serious.’ That one put me over the edge. I’d probably heard one pack of beats and liked some things, but "Laraaji" made me excited to write and record, to take it to the next step.

Another that had the same spark for me was the beat called "Longjohns". It made me really, really excited. I thought, ‘I’ve got to write this song; it has to be this way.’ But I just couldn’t find a way to start. When I did, I recorded a demo at our studio, and I wasn’t satisfied; it didn’t work out in the real world like it did in my mind. So that took a couple of drafts to get to the finished version.

billy woods: It’s interesting. Some of those hit right away. I’d say the feeling on "Laraaji" was immediate; we hit each other up the same way. It came from the third and final folder of beats Alchemist sent us during the process. There were other beats after that, but those were in person in the studio. I can echo ELUCID's feeling on "Laraaji" we reached out to each other as soon as we got it.

For me, "Moonbow" was one of those. I wrote it in the studio and recorded it way back before ELUCID. He didn’t do a verse or anything; it was just me on the track for a significant amount of time. "Scandinavia" was another I was instantly drawn to. I remember thinking, ‘Alright, let’s keep this out there,’ and Al was really big on doing that one. And for me, "u know my body" was another — it was about the moment I heard it.

woods, you reference the Pinochet death flights on "Moonbow". What was it about that obviously horrific historical event that resonated?

billy woods: Sort of touching on fascism — that’s the association that came in. It’s like [starts rapping] "People are fed from the palm of a tyrant. Michelin star — you dine in near silence, silverware rattling, chewing and sighing… exquisitely slow violence." And then, thinking about it… that image just came to me, you know.

There's also a sense of yearning in that track ("I miss you like the regime toppled").

billy woods: Yeah, I thought about when they open the plane doors — the cargo bay — to the throw; you’d be looking out, probably at the sun coming up over the South Atlantic. It must be crazy: terrible and beautiful at the same time.

Your previous record We Buy Diabetic Test Trips felt very much like Armand Hammer reckoning with, or maybe reflecting on, the material world. By comparison, Mercy has a more shamanistic, dream-like quality: it starts with "Laraaji" kind of shell shocking the listener, but then it gradually decompresses towards a reprieve, ending with this really nostalgic track ("Super Nintendo").

billy woods: I can see that shamanistic perspective — there are certainly elements of it. The comparison I made is that Haram feels a bit claustrophobic, whereas this one moves through a lot of different moods and feels more expansive and open to me.

No lie, I feel "Calypso Gene" is one of the outright prettiest things Armand Hammer has ever done.

ELUCID: Yeah. With that particular song, just hearing that beat brought immediate inspiration. I kind of knew how I wanted to flesh it out once I had that one line, ‘take me to the water.’ I knew I wanted a chorus of vocals — wasn’t sure who it would be — but I wanted to add the additional textures I heard in the track: melodically strong but really understated. We did a very understated version without any additional vocals, and that was Alchemist’s favorite version in the end, but we spruced it up with some other colors. We landed on a compromise; the vocalists Silka and Cleo Reed did a fantastic job on there.

The Alchemist gives you folders with beats, but how much was he involved with guiding the tracks to their final form on Mercy?

ELUCID: Generally, if we weren’t working in person, we’d send everything to Alchemist and he’d restructure it his way. I like working with a producer who can really produce like that. A good example is "California Games": another version exists with Earl Sweatshirt, which we recorded in LA over a completely different beat. Afterward, Alchemist produced the song, flipped it, and gave us what you hear now, and it’s the better version. The first one was really good, but the second is where it’s at.

How did you go about embellishing Mercy with additional audio recordings, as kind of the connective tissue?

ELUCID: Yeah, we love that collage of sounds that ties songs, ideas, and moods together — and sometimes doesn’t tie them so much as closes one door and opens another. We love YouTube; we’re all media consumers, and sources come from everywhere. For Haram, I won’t say exactly, but I watching a lot of dumb shit. During that recording — don’t judge me, it was COVID — I’d watch guys in remote places build homes from dirt with simple tools, sped up so a huge project finished in twenty minutes.

I got addicted: no talking, no music, just birds, mosquitoes, and the sound of tools. I sampled a bunch of that for Haram and flipped it with effects. For this record, Mercy, I was also inspired by a movie called Statues Hardly Ever Smile, made in the ’70s about a kids’ art program at the Brooklyn Museum. The kids designed their own summer curriculum, and the documentary captured it. When I put it on, the minimal score and the museum’s reverberating, hollowed-out atmosphere grabbed me. The things those teenage kids were saying are often really profound, in simple ways. We sampled a couple pieces from it.

This final question – more like an elaborate thought– may be a bit of a stretch. Back to the closing track "Super Nintendo", it hit me in a profound way. Especially compared with how Mercy starts with "Laraaji", woods had this line where 'everybody's a camera man.' We're so mired and overexposed in this technocracy, whereas the Super Nintendo was a piece of technology that inspired childlike imagination or escape. For some reason, I had to think of that Tommy Lee Jones line in Men In Back: "The only way these people can get on with their happy little lives is that they do not know about it." Well, now, whether we like it or not, we all kind of know about it. And to me, Mercy kind of feels like a record that veers between that sense of oblivion and that sense of knowing.

billy woods: For me, that song is about a certain time and energy, depending on where you take it. I can’t say I didn’t see or know those things — given my circumstances and where I grew up — but regardless of what you saw, there are things you don’t think about or you contextualize differently when you’re young. It’s about the dualities I see when I look back on my youth and into my twenties: bad things, new things, friends doing things (good and bad), experiencing life, becoming your own person. You move from being a kid toward adulthood; you have more control over your decisions, and you’re discovering what that means as you go. You realize, ‘It’s just me out here doing this,’ and all that implies in my life — and then I carry that into what I see now.

ELUCID: When I think about that song, there’s a lot of nostalgia. I’m always moving with the music. woods came up with the title "Super Nintendo" but when I hear the music I think of video games: it has an 8- or even 16-bit quality to the melody, looping like a title screen. I got that from the jump. It makes me think of myself as a kid — curious, nosy, eavesdropping, reading everything, watching everything. These days it’s similar, but I have to remind myself not to be rigid, to let things happen to me like I did as a kid. When I think about "Super Nintendo" I think about that.

Order your copy of Mercy here at the Backwoodz Studioz catalog.

What do you think?

Show comments / Leave a comment