I was about eight years old when I realized the music my dad played in our car and around our house was very different from what my friends' parents listened to. It was the 90s, and Red Hot Chili Peppers, Nirvana, and Alanis Morissette were on loop in most carpools. But when my dad picked us up, it was Eek-A-Mouse, The Mighty Diamonds, The Specials, and The Clash. He is one of those people who believe The Clash was the most important band of all time. It was ska, dancehall, dub, rocksteady, and reggae.

It was different, and he was obsessed and deeply passionate about it. So much so that he and my mom went to Jamaica for their honeymoon in 1986, and he even brought along a tape recorder so he could capture local radio broadcasts. The tapes are still sitting in his attic. I can safely say my passion for music came from him, and even though I branched out into other genres, I still have deep respect for his admiration of this music and this moment in history.

Something that has always stood out to me is how this genre has been portrayed over the years, and how it has been almost universally shunned by critics. In the fifty-some years since most of these bands hit the scene, reggae has developed a stereotype in the States as the “stoner dude” archetype that has been played out in movies and TV shows for years. You know the guy: smokes a lot of weed, wears a Bob Marley shirt that could just as easily be a Sublime shirt, grows his hair into locs, and claims to be Rastafarian without any real understanding of what that means. Think Jim Carrey’s In Living Color song “Imposter” or The Lonely Island’s “Ras Trent”.

And sure, all genres are ripe for parody, but with reggae it often feels like it goes further, with a sense that the music itself is somehow unserious. The irony, of course, is that most reggae songs address extremely serious realities such as poverty, political injustice, starvation, and the legacy of slavery. In many ways, reggae’s evolution mirrors that of early jazz in the United States. The difference is that jazz is now regarded as foundational to music history and highly respected in critical circles. While Bob Marley’s legacy has undeniably secured reggae’s place in history, the genre as a whole is rarely given the same recognition.

I am not claiming to be an expert here. Far from it. But for me, it was always just about the music. This music is my childhood. A pure appreciation for the uniqueness of the dub echoes and sound effects being made decades before electronic capabilities, the offbeat chords, the 4/4 rhythm, the struggle and vulnerability in the lyrics, and the genre’s overlooked influence on music as a whole.

This is not meant to be a critique or a history lesson, though there is a little of both. Mostly, it is an appreciation for artists and albums that deserve more recognition.

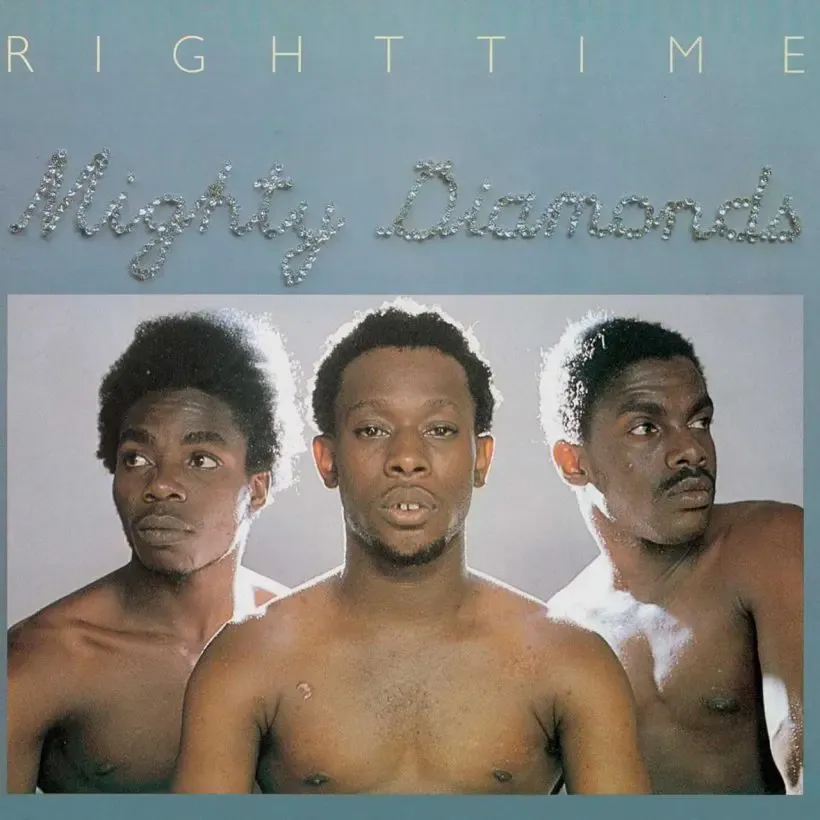

Mighty Diamonds – Right Time (1976)

Often called the “Motown of Jamaica,” Mighty Diamonds struck gold with their 1976 debut Right Time, though that gold was vastly undervalued. Hailing from Trenchtown, Kingston, the trio of Donald “Tabby” Shaw, Fitzroy “Bunny” Simpson, and Lloyd “Judge” Ferguson established a sound uniquely their own: smooth, melodic harmonies with roots in ‘60s soul, channeled through Rastafarian consciousness. With the world’s attention shifting toward reggae following Bob Marley’s international breakout, Virgin Records signed the group and released Right Time, featuring tracks the band had honed since forming in 1969.

The album saw global success, but it was followed by the commercial disappointment of their sophomore record Ice on Fire, and the Mighty Diamonds faded from mainstream attention. They returned to the spotlight in 1982 with “Pass the Kouchie”, a ganja anthem that was sanitized and popularized in the U.S. by Musical Youth’s “Pass the Dutchie”.

Still, Right Time captures the Mighty Diamonds at their most raw, righteous, and radiant. Tabby’s voice glides with clarity and conviction over Bunny and Judge’s perfectly stacked harmonies. Songs like “I Need a Roof” and “Why Me Black Brother Why” speak directly to the struggles of life in Trenchtown. But instead of despair, they offer strength and defiance.

The group channels the spirit of Marcus Garvey, the Jamaican activist and orator who championed Black pride, self-sufficiency, and Pan-Africanism. His influence is front and center on “Them Never Love Poor Marcus”. Recorded before the rise of digital production, the album features real musicianship with deep, heavy bass, and live drums that move you.

While Right Time may have only briefly lit up the charts, it remains a foundational roots reggae record. The only track I tend to skip, and it’s no fault of the song itself, is “Go Seek Your Rights.” The somber chorus, “No man is an island, no man stands alone,” has always haunted me. Every time we listened to it my dad would insist that he wanted this song played at his funeral, and I know one day I will have to insist on following through with that request, even if other family members object.

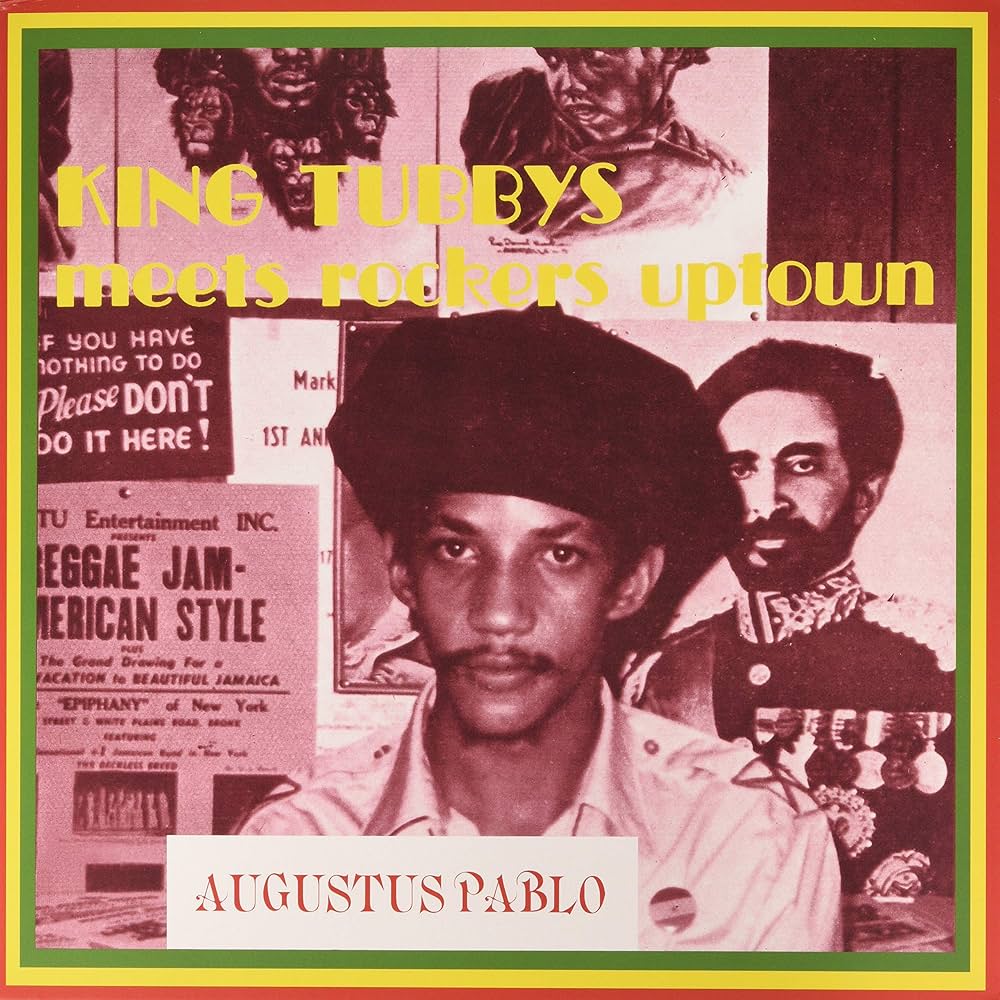

Augustus Pablo & King Tubby – King Tubby Meets Rockers Uptown (1976)

Augustus Pablo was a producer and melodica player who recorded King Tubby Meets Rockers Uptown with an all-star cast of reggae musicians before teaming up with King Tubby to turn it into a masterpiece of pure dub. Dub was already an established genre at the time, but this record stands as one of its quintessential examples, two musically gifted innovators coming together to create magic. Pablo was known for his melodica, an instrument you might not be familiar with. It’s basically a small hand-held keyboard that you blow into to generate sound. If you’re a fan of Gorillaz, you’ve heard it; Damon Albarn often uses the melodica, citing Pablo as a direct influence. In a 2000 interview with the Sydney Morning Herald, Albarn said Pablo was responsible for “really opening up Jamaican music to me.”

King Tubby, on the other hand, is considered the godfather of dub. He helped pioneer the genre and essentially created the iconic echo and reverb effects that are now synonymous with it. Tubby’s path was unique: he started as an engineer fixing radios and sound systems, which led him to run a pirate radio station and eventually open his own studio. His hands-on tinkering with equipment allowed him to bend and manipulate sounds in ways no one had thought possible, creating hypnotic, spacey textures layered over bass that felt like it was pulled from another world.

When Pablo and Tubby joined forces on Rockers Uptown, the result was magnetic. The album is mostly instrumental, though it does include samples from artists the duo had worked with, such as the late reggae pioneer Jacob Miller. His song “Baby I Love You So”, originally produced by Pablo, is transformed here into something one of a kind. Over the years, Rockers Uptown has gained the recognition it deserves. The title track even landed at number 266 on Rolling Stone’s list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time. And it’s no wonder — the drums absolutely explode, like someone pounding away with a vengeance on over-tightened skins. My dad used to air-drum along on the steering wheel every time that part came on… he probably still does.

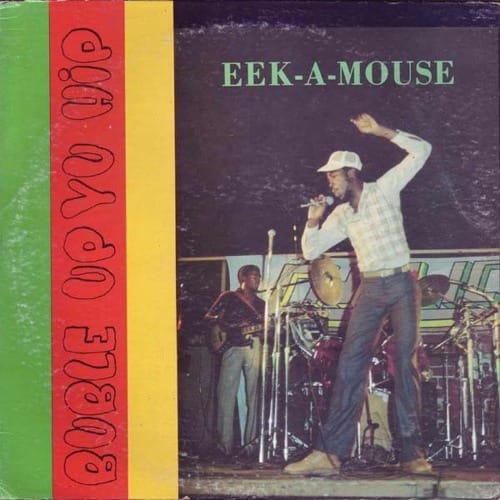

Eek-A-Mouse – Bubble Up Yu Hip (1980)

Controversial from the start with his breakout single “Wa-Do-Dem” with the lyrics “Say me love me virgin girl”, Eek-A-Mouse made waves at Reggae Sunsplash 1982, arguably the most impactful reggae festival of all time. Before bringing him on stage, the presenter (and DJ host) explained that his radio director couldn’t even handle the lyrics.

Four weeks later, the single had climbed to number one. With his high-pitched vocals, playful scatting and toasting — “biddy biddy beng, biddy bong, riddim on the track-a, mouse upon the mic-a” — and his bold, often controversial storytelling, Eek was a recipe for success. He became the standout performance at that year’s Sunsplash, which carried a heavy tone after Bob Marley’s recent passing. The Mouse, however, brought the heat and lifted the festival’s spirits.

The virgin motif carried into other tracks like “Every Girl Is a Virgin” and “Virgin Girl”. Tall, confident, eccentric, and decked out in wild stage costumes, Eek carried himself like a superstar. There wasn’t anyone like him in reggae then, and there hasn’t been anyone quite like him since. His debut Bubble Up Yu Hip dropped on the legendary Greensleeves label, offering the first real glimpse of his personality starting to shine through.

From 1980-87, Eek released a run of albums stacked with hits, each one building on the last. Backed by the Sagittarius Band, he paired compelling vocal delivery and sharp lyrics with a group that could push his music into dub territory.

On his next album, the breakthrough Wa-Do-Dem, the track “Noah’s Ark” stood out, especially in its extended version. The song kicks into a full dub section right after the sound effect of a cassette tape melting down in the deck. Anyone who ever lived through a tape spinning out knows the sound – it’s brutal. Cruel joke or not, it was the perfect gateway into the dub side of an already heavy bass track. Eek’s voice, when echoed, created its own kind of dub effect.

Because of that playfulness, Eek-A-Mouse became my favorite growing up. Eek-A-Mouse was also my first concert. In 1999, he played the San Diego Del Mar County Fair. I was 11. Before the show, we actually ran into him walking around with his kids. My dad introduced me, saying, “Ricky, I want you to meet a legend.” Eek, all 6’6” of him, crouched down, shook my hand, and sang: “Rickiiieee, wadadem, baddanono, biddy biddy bong.” That was it. Favorite artist back then. Even if none of my friends at school had a clue who I was talking about the next day.

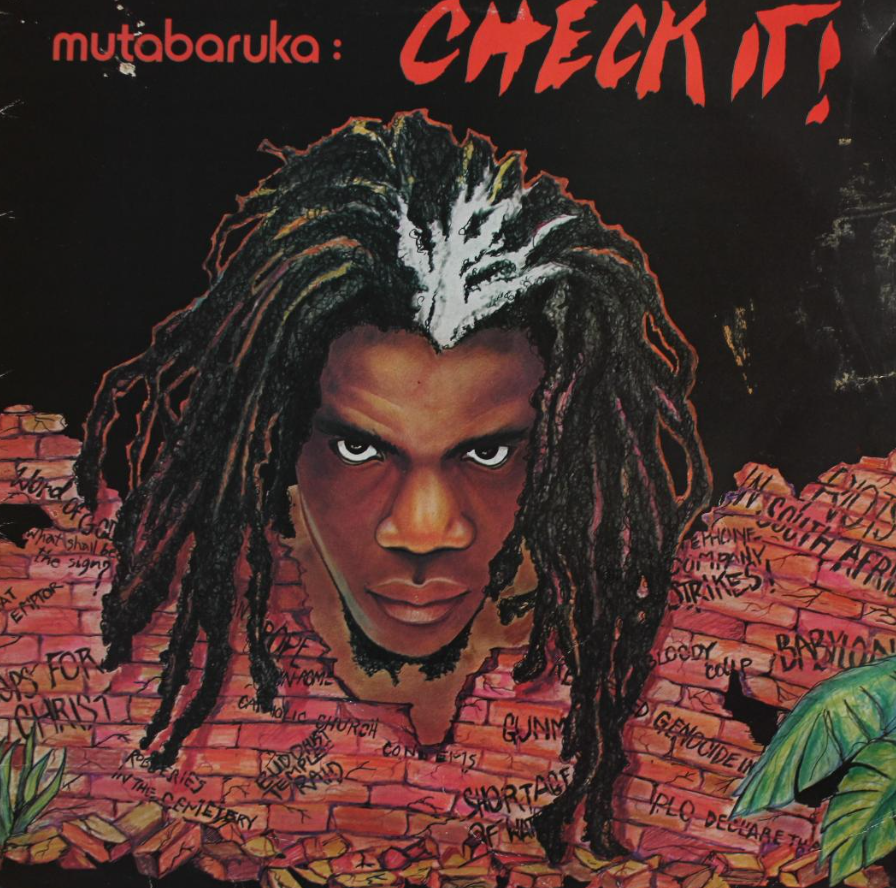

Mutabaruka – Check It (1982)

Born Allan Hope, he adopted the Rwandan name Mutabaruka, meaning “one who is always victorious.” His creative life has been prolific, and not just in music. Hope began as a poet, publishing in the Jamaican magazine Swing, writing on politics, oppression, racism, religion, and poverty. Soon, he took his words to the stage, performing live with the band Truth, fusing poetry with dub in a hybrid that was confrontational and unforgettable.

His debut album Check It! pulls no punches, much like the illustrated glare he gives on the cover. It tackles unsafe life in “Whiteman Country,” murder in the streets, the Angolan Civil War, a black man joining the Ku Klux Klan, and the fraudulence of the entire political system. Mutabaruka preached anti-colonialism and black consciousness, a message that resonated deeply with Jamaicans, though not with the political party in power at the time — which only gave his words more weight. His message wasn’t about easy listening. It was about movement and revolution.

Still, the backing band never missed. Heavy dub bass, strange sonic textures, and militant delivery gave the record its fire. Mutabaruka barked out orders like a drill sergeant, demanding change. To put it in Western terms: Mutabaruka is to reggae what Rage Against the Machine are to rock. Both weaponized music into a platform for revolution.

My dad tended to skip this one in the carpool rotation. The record if full of raw lines about race, identity, and displacement — powerful stuff, just not exactly fit for a minivan of ten-year-olds on the way to school. But my dad and I loved Mutabaruka. His songs were some of my first exposures to racial injustice and opened my mind to inequality in the world.

In middle school, I was assigned to read a poem aloud to the class. I chose Mutabaruka’s 1986 piece “Dis Poem”, one of his most popular works, which came out a few years after Check It! I’ll never forget standing in front of a classroom of preteens declaring: “Dis poem is vexed about apartheid racism fascism / The Ku Klux Klan riots in Brixton Atlanta / Jim Jones / Dis poem is revolution against 1st world 2nd world / Dis poem is revoltin against 1st world 2nd world.” I thought I was about to blow their prepubescent minds. Instead, I was met with a room full of blank stares.

Lee “Scratch” Perry – Trojan Dub Box Set (1998)

Lee “Scratch” Perry and King Tubby are essentially the godfathers of reggae dub. Both producers stamped their unmistakable signatures onto every track they touched, reshaping the sound of Jamaican music in the process. Perry in particular was eccentric and wildly experimental, treating recording as a spiritual act rather than a technical one. He pushed past the limits of traditional studio work, burying microphones beside palm trees and pounding on the trunk to capture a bass-drum thump, for example, and let sessions unfold in real time instead of trying to control every detail. That looseness gave his productions a rough, demo-like quality that dove deeper into bass, echo, samples, and atmosphere. He lived inside reverb.

At one point or another, Perry worked with nearly every major reggae artist under the sun: early Bob Marley & The Wailers, The Heptones, The Upsetters, Max Romeo, and countless more. Much of his groundbreaking “dub” sound came out of his legendary backyard studio, The Black Ark, which he built in 1972 and later burned down himself in a fiery fit of frustration. A quick look at Perry’s Wikipedia discography reveals an almost absurd 80-plus album credits, he truly had his fingerprints all over reggae history.

His certified classics include The Upsetters’ Super Ape, Max Romeo’s War Ina Babylon, and Perry’s own Arkology. But the Perry my dad and I bonded over didn’t come directly from those albums, it came from the many Trojan Records box sets we had on heavy rotation.

Before the internet, Napster, YouTube, and streaming, mixes were hard to come by. Unless a record label released a compilation or you stumbled across a solid movie soundtrack, you bought albums based on a couple of singles and hoped for the best. Trojan’s box sets were an asset to showcasing reggae to the world. In the ’90s, they were essential: deep cuts, massive tracklists, and themed collections spanning reggae, rocksteady, and ska, hundreds of songs packed onto CDs.

Those box sets were a staple in my house, and they often showed up as gifts under the Christmas tree. If you’re looking for an easy entry point into Perry’s universe (or dub in general), the Trojan Dub Box Set is hard to beat. It’s stacked with classics, including some of his best tracks with The Upsetters.

If you’ve enjoyed the artists mentioned above, you should also check out Sister Nancy — best known for her classic “Bam Bam”, which has been sampled and referenced across countless hip-hop tracks. Big Youth’s Screaming Target is another essential, aptly named for the signature scream Manley Augustus Buchanan weaves throughout the record. U-Roy, a pioneer of toasting (a freestyle, rhythmic form of talking or rhyming over a beat with its own unique, often monotone flow), deserves attention as well. And you can’t overlook Toots and The Maytals, who are credited with coining the term “reggae” in their 1968 single “Do the Reggay”, giving the burgeoning musical movement not only a name but a clear identity as it entered the world.

There’s so much more to explore, and as I mentioned earlier, you can’t go wrong diving into a Trojan box set to sample the best of these subgenres before branching off on your own. There is far more to reggae than just Bob Marley – and no shade to his music! I love “Small Axe” as much as the next person. But if you’ve ever dismissed reggae because Marley wasn’t your thing, I hope this piece serves as an invitation to explore the genre’s rich, expansive history.

Revisiting these albums and reflecting on how they shaped the connection between my dad and me has been genuinely heartwarming. Now that I’m a father myself, I’m realizing just how special it is to share a bond built on passion. Of course there are limits; you never want to overinfluence your kid. But when there’s a shared joy, it becomes something unforgettable. And being able to share your passions vulnerably gives your child permission to explore theirs with the same openness.

In high school, I drifted away from reggae, dub, and ska, and dove headfirst into the hardcore, post-hardcore, and emo scenes of the early 2000s. I went all in: skinny jeans, youth medium band tees, the whole “scene” identity, practically living at the local venue. But if I hadn’t grown up with a model of loving music that wasn’t the status quo, of being encouraged to follow what moved me, I don’t know if I would’ve taken that path. I don’t know if my love of music would’ve endured long enough to lead me here, writing this article as a music journalist. My dad’s love of reggae is what set me on this road, and I’m grateful for it.

What do you think?

Show comments / Leave a comment